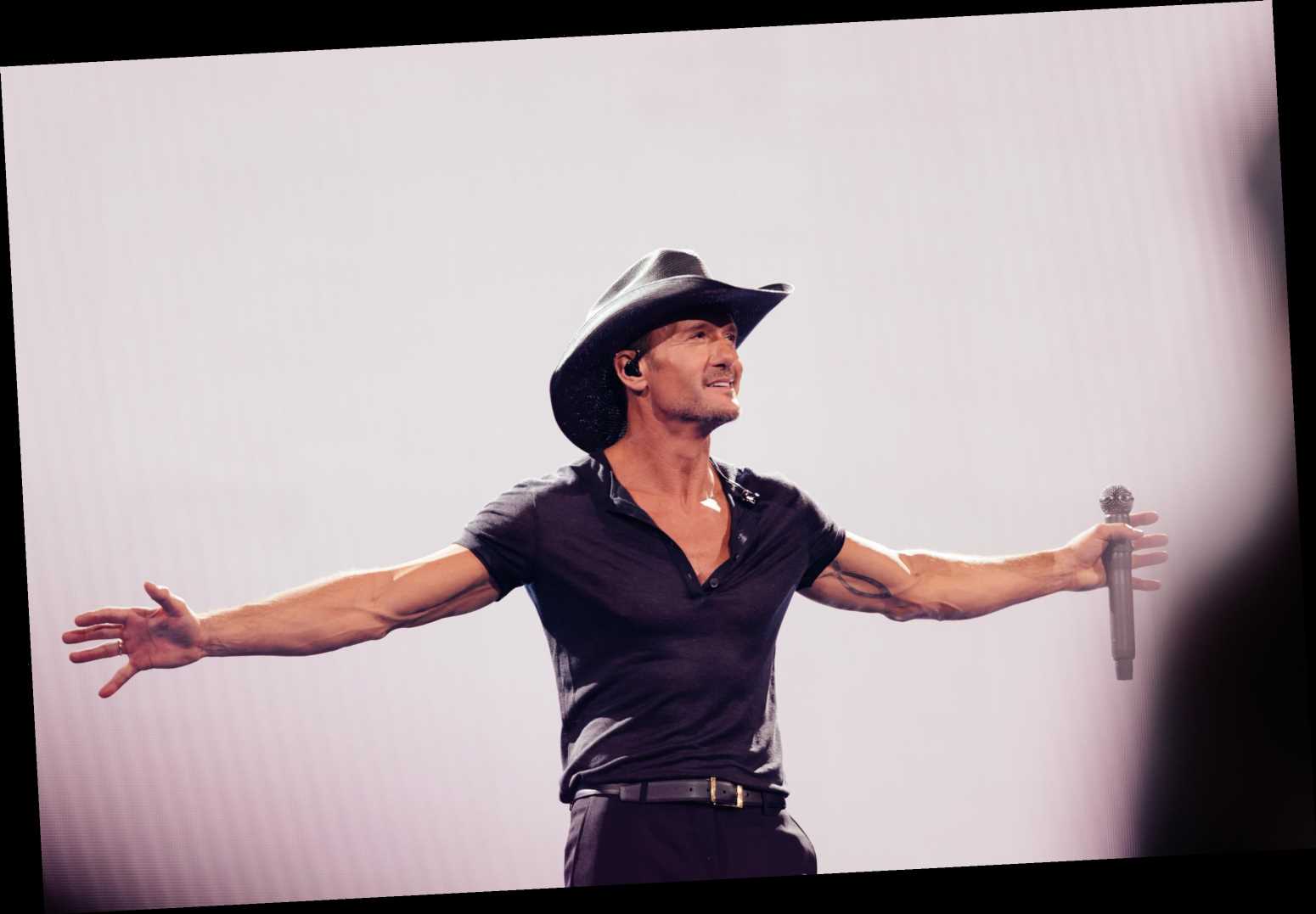

For a long time, Tim McGraw thought he could benefit from taking six months off. Even before music became his career, he had always had a job; when country stardom took over, his workload only increased. He was perpetually on the road, supporting his albums and hits like “My Best Friend,” “I Like It, I Love It,” and “Real Good Man.” But when 2020 and the pandemic set in, he was forced to test out his theory.

“I was sort of like, alright, I’m getting a year off without realizing it, and maybe I’ll enjoy it,” McGraw tells Rolling Stone. “Two weeks into it, I got so antsy and I’m ready to play a show, so I’m trying to figure out what to do.”

Instead of climbing the walls, the hyperfit McGraw found comfort in being present at home with his wife Faith Hill and, for an enlightening month-long stretch, their three daughters. Their youngest just graduated from high school — with no ceremony — and these days they aren’t all together at home very often.

“You get to discover things about each other that maybe you didn’t even realize, or only knew cursory as a parent or as a child,” he says. “And being able to spend this time together has given us some insight on our girls and an appreciation for how smart they are, and how adjusted they are, and how articulate they are.”

In a similar way, McGraw’s new album Here on Earth finds him praising the bond of family and exploring the intricacies of relationships, while finding contentment and purpose along the way.

McGraw had all of his new songs selected and recorded prior to the pandemic, having begun the process after his Soul II Soul Tour with Hill and their duets album, The Rest of Our Life. With a nearly five-year gap between solo albums, he wanted to make something, as he says, “where you could look at life from a 40,000-foot view but you could also dive down and get intimate on some of these songs.”

The pandemic changed things slightly, forcing McGraw and longtime producer Byron Gallimore to take a second look at everything they’d recorded.

“We gotta see if the mixes hit the emotional points that we feel now as opposed to what we felt then,” he says. A few were remixed in subtle ways, others met the moment.

Others, like McGraw’s current single “I Called Mama,” got some added weight from the fact that so many people are separated and feeling anxious.

“Before Covid, it would be a song about losing someone and instantly calling the person that grounds you the most and knows you the best and can set you at ease,” he says. “After Covid hit, that song had such a broader scale to it, because it was really about everything that was going on in the world and who are the people — not just your mom — that ground you and know you.”

At 53, McGraw is something of an elder statesman among country artists still enjoying radio success. Keith Urban and Kenny Chesney are in a similar place at 52. Unlike a lot of his younger contemporaries, though, McGraw has largely stayed away from disposable party songs (with some exceptions like “Truck Yeah”) and carefully selected material that conveyed gravitas (“Live Like You Were Dying”) or a convincing blend of toughness and tenderness (“One of Those Nights”).

True to form, McGraw kicks off Here on Earth with “L.A.,” a love song in the key of Glen Campbell and Jimmy Webb that depicts a “boy in faded jeans and cowboy boots” feeling totally out of place in California but happy to stick it out for the woman he loves. McGraw tapped string arranger David Campbell for the cinematic, bittersweet accompaniment.

“That’s probably my favorite record I’ve ever made in my career,” McGraw says. “I had that string section, that intro string section in my head from the very first time I heard the demo.”

McGraw examines various stages of relationships (and their conclusions) in “Hard to Stay Mad At,” “If I Was a Cowboy,” and the truck-full-of-memories song “7500 OBO,” which references past McGraw hits “Where the Green Grass Grows” and “Shotgun Rider.” One of his strongest this time around is “Hold You Tonight,” which comes with the lived-in feel of the work required to create an equal, supportive partnership. “I don’t ever want you to wonder/Who you might have been on your own,” he sings.

“At this stage of my life and this stage of my marriage, with our kids leaving, and all the things that go on when you’re in your fifties, that song took on an entirely different meaning to me,” McGraw says. “It almost seemed like a song you couldn’t really sing unless you had that much life under your belt.”

That idea of being grounded and content pops up in several places. The title track is about finding purpose and meaning in this life, while “Gravy,” written by Tom Douglas, Allen Shamblin, and Andy Albert, is about feeling satisfaction when “dreaming of the cherry-red GTO/Even if I’ll never get it.” Album closer “Doggone” pays tribute to the unflagging companionship of man’s best friend. The song “Hallelujahville,” another Douglas co-write, looks back to McGraw’s small-town Louisiana origins and how much they’ve stayed with him even as a famous, wealthy person.

“’Hallelujahville’ reminded me of the places I grew up and the people I grew up with, but also it’s sort of an existential thing,” he says. “It reminded me of how much all of us are grounded to the place we grew up in and how much the place we grew up in is a part of us, and how much that is ingrained in us.”

There’s also an element of “Hallelujahville” that makes room for all kinds of thought. “Don’t call us small town, never have been, never will,” he sings in one particularly defiant line.

“You can’t paint us all with the same brush,” McGraw says. “And not to be political, but no matter what your beliefs are, you can’t take that away from me.”

Even so, McGraw has regularly stood up for more progressive causes. In June, as protests over racial justice were happening all over, he wrote a measured Facebook post about his own privilege and calling for change, without explicitly mentioning Black Lives Matter. “I don’t know how it feels to be black in America,” he wrote. “I don’t know how it feels to walk down the street at night and feel eyes of suspicion. I don’t know what it’s like to carry the worry for my child simply because they are black. I won’t pretend to.”

“To be genuinely moved by something and try to say something that’s like, hey, I’m not attacking anyone, but this where we’re at,” he says. “This is how I feel. I can’t make judgments on other people’s lives because I haven’t lived their lives. But I know there are changes that need to be made. I thought that was the best way I could say it.”

But those ultra-topical moments are rare on Here on Earth, and there are carefree, lighthearted numbers to balance things out. “Good Taste in Women” is a danceable humblebrag, while the propulsive “Chevy Spaceship” lives up to its name with a countdown sequence and otherworldly effects.

“It just seemed so different and so fresh,” McGraw says. “At the same time there’s some sort of teenage angst in it. I wanted to play ‘Chevy Spaceship’ so bad this summer. We had such a great show idea for it.”

Instead, McGraw will host the Here on Earth Experience on Friday, preceded by performances from erstwhile tourmates Ingrid Andress and Midland. The special, which streams live at 7 p.m. CT, costs $15 and features intimate performances as well as a look into making the album.

“What’s the hybrid of saying, if you took an HBO music show or MTV Unplugged, how do you marry those things together and get the production value that’s really cool and interesting, that will be worth it to the fans because we may have to do this for a while,” he says.

As for how long, that’s anyone’s guess at this point. McGraw’s eager to get back out there, but he doesn’t want to make any predictions about when. For now, he’ll keep making the most of his time off.

“I’m gonna leave it to the people who know what they’re talking about and [go out] when we can be as safe as we can possibly be,” he says. “Then I’m onboard to go and play my heart out as long as I possibly can.”

Source: Read Full Article