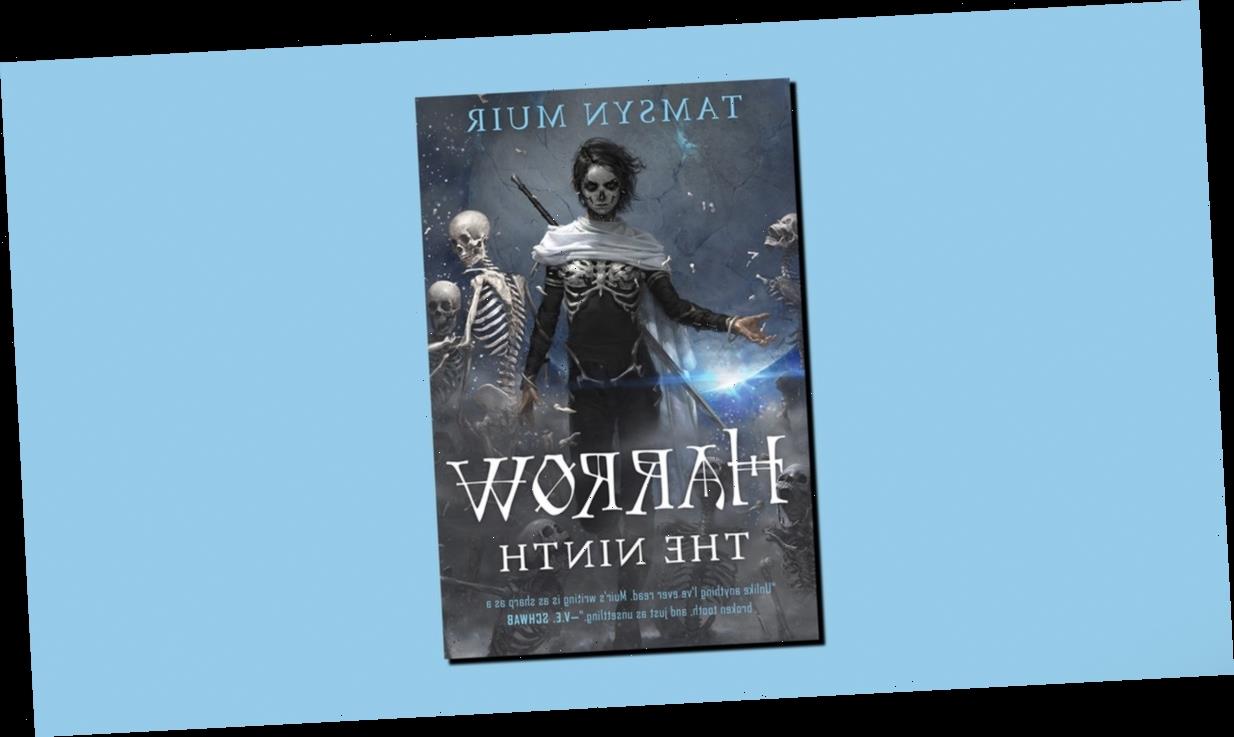

Gideon the Ninth‘s riveting tale of lesbian necromancers in space is getting a sequel in 2020, and you can start reading it right now. Bustle is pleased to reveal the gorgeous cover for Harrow the Ninth, along with an exclusive excerpt from the novel’s prologue. Keep scrolling to read a spoiler-free explainer of Tamsyn Muir’s inventive new series, and check out the opening passage of Harrow the Ninth.

In the world of Gideon the Ninth, eight houses of necromancers in service to the Emperor receive a summons, demanding they send their heirs and cavaliers — read: necromancers and bodyguards — to Canaan House. The necromancer heirs have the opportunity to become Lyctors — the Emperor’s elite warriors — but uncovering the secrets of Lyctorhood will prove dangerous in a competition without any rules.

Into this fray, the Ninth House sends Harrowhark Nonagesimus and Gideon Nav. To say that these childhood rivals don’t care much for one another would be an understatement. Gideon, the Ninth House’s indentured servant, wants nothing more than to leave its society and go off to war. Meanwhile, Harrow, as the Reverend Daughter of the already mistrusted Ninth House, is protecting an old secret that could easily cost her everything. Her parents have long been dead, and she has ruled in their stead, preserving and puppeteering their corpses, for years.

Arriving at Canaan House after making a tentative truce with each other, Harrow and Gideon find themselves thrust into a sweeping murder mystery that begins to claim the lives of other necromancers and cavaliers, one by one.

Gideon the Ninth is available today. Keep scrolling to read an exclusive excerpt from Harrow the Ninth, out on June 2, 2020.

PROLOGUE: THE NIGHT BEFORE THE EMPEROR’S MURDER

Your room had long ago plunged into near-complete darkness, leaving no distraction from the great rocking thump — thump — thump — of body after body flinging itself onto the great mass already coating the hull. There was nothing to see — the shutters were down — but you could feel the terrible vibration, hear the groan of chitin on metal, the cataclysmic rending of steel by fungous claw.

It was very cold. A fine shimmer of frost now coated your cheeks, your hair, your eyelashes. In that smothering dark, your breath emerged as wisps of wet grey smoke. Sometimes you screamed a little, which no longer embarrassed you. You understood your body’s reaction to the proximity. Screaming was the least of what might happen.

God’s voice came very calmly over the comm:

“Ten minutes until breach. We’ve got half an hour of air con left… after that, you’ll be working in the oven. Doors down until the pressure equalizes. Conserve your temp, everyone. Harrow, I’m leaving yours closed as long as possible.”

You staggered to your feet, limpid skirts gathered in both hands, and picked your way over to the comm button. Scanning for something damning and intellectual to say, you snapped: “I can take care of myself.”

“Harrowhark, we need you in the River, and while you are in the River your necromancy will not work.”

“I am a Lyctor, Lord,” you heard yourself say. “I am your Saint. I am your fingers and gestures. If you wanted a Hand who needed a door to hide behind — even now — then I have misjudged you.”

From his far-off sanctum deep within the Mithraeum, you heard him exhale. You imagined him sitting in his patchy, worn-out chair, all alone, worrying his right temple with the thumb he always worried his right temple with. After a brief pause, he said: “Harrow, please don’t be in such a hurry to die.”

“Do not underestimate me, Teacher,” you said. “I have always lived.”

You picked your way back through the concentric rings of ground acetabulum you had laid, the fine gritty layers of femur, and you stood in the centre and breathed. Deep through the nose, deep out the mouth, just as you had been taught. The frost was already resolving into a fine dew misting your face and the back of your neck, and you were hot inside your robes. You sat down with your legs crossed and your hands laid helplessly in your lap. The basket hilt of the rapier nudged into your hip, like an animal that wanted feeding, and in a sudden fit of temper you considered unbuckling the damn thing and hurling it as hard as you possibly could to the other side of the room; only you worried how pitifully short it would fall. Outside, the hull shuddered as a few hundred heralds more assembled on its surface. You imagined them crawling over each other, blue in the shadow of the asteroids, yellow in the light of the nearest star.

The doors to your quarters slid open with an antique exhalation of gas levers. But the intruder did not set off the traps of teeth you’d embedded in its frame, nor the gobbets of regenerating bone you had gummed onto the threshold. She stepped over the threshold with her cobwebby skirts rucked high on her thighs, teetering like a dancer. In the darkness her rapier was black, and the bones of her right arm gleamed an oily gold. You closed your eyes to her.

“I could protect you, if you’d only ask me to,” said Ianthe the First.

A tepid trickle of sweat ran down your ribs.

“I would rather have my tendons peeled from my body, one by one, and flossed to shreds over my broken bones,” you said. “I would rather be flayed alive and wrapped in salt. I would rather have my own digestive acid dripped into my eyes.”

“So what I’m hearing is… ‘maybe’,” said Ianthe. “Help me out here. Don’t be coy.”

“Do not pretend to me that you’re here for anything other than to look after an investment.”

She said, “I came to warn you.”

“You came to warn me?” Your voice sounded flat and affectless, even to you. “You came to warn me now?”

The other Lyctor approached. You did not open your eyes. You were surprised to hear her crunch through your metrical overlay of bone, to kneel without flinching on the grim and powdery carpet beneath her. You could never sense Ianthe’s thanergy, but the darkness seemed to give you an immense attunement to fear. You felt the hairs rise on the back of her forearms; you heard the hammering of her wet and human heart, her scapulae urging together as she tensed her shoulders. You smelled the reek of sweat and perfume: musk, rose, vetiver.

“Nonagesimus, nobody is coming to save you. Not God. Not Augustine. Nobody.” There was no mockery in her voice now, but there was something else; excitement, perhaps, or unease. “You’ll be dead within the first half-hour. You’re a sitting duck. Unless there’s something in one of those letters I don’t know about, you’re out of tricks.”

“I have never been murdered before, and I truly don’t intend to start now.”

“It’s over for you, Nonagesimus. This is the end of the line.”

You were shocked into opening your eyes when you felt the girl opposite cup your chin in her hands — her fingers febrile, compared to the chilly shock of her gilded metacarpal — and put her meat thumb at the corner of your jaw. For a moment you assumed that you were hallucinating, but that assumption was startled away by the cool nearness of her, of Ianthe Tridentarius on her knees before you in unmistakable supplication. Her pallid hair fell around her face like a veil, and her stolen eyes looked at you with half-beseeching, half-contemptuous despair: blue eyes with deep splotches of light brown, like agate.

Looking deep into the eyes of the cavalier she murdered, you realised not for the first time, and not willingly, that Ianthe Tridentarius was beautiful.

“Turn around,” she breathed. “Harry, all you have to do is turn around. I know what you’ve done, and I know how to reverse it, if you’d only ask me to. Just ask; it’s that easy. Dying is for suckers. With you and me at full power, we could rip apart this Resurrection Beast and come away unscathed. We could save the galaxy. Save the Emperor. Let them talk back home of Ianthe and Harrowhark — let them weep to speak of us. The past is dead, and they’re both dead, but you and I are alive.

“What are they? What are they, other than one more corpse we’re dragging behind us?”

Ianthe’s lips were cracked and red. There was naked entreaty on her face. Excitement, then, not unease.

This was, as you understood it dimly, the psychological moment.

“Go fuck yourself,” you said.

The heralds came plopping down onto the hull like rain. Ianthe’s face froze back into its white and mocking mask, and she dropped your jaw — untangled her restless fingers and her awful gold-shod bones.

“I didn’t think this was the time for dirty talk, but I can roll with it,” she said. “Choke me, Daddy.”

“Get out.”

“You always did think obstinacy the cardinal virtue,” she remarked, quite apropos of nothing. “I think now, perhaps, you should have died back at Canaan House.”

“You should have killed your sister,” you said. “Your eyes don’t match your face.”

Over the comm, the Emperor’s voice came, just as calm as before: “Four minutes until impact.” And, as though a tutor chiding inattentive children: “Make sure you’re in place, girls.”

Ianthe turned away without violence. She stood and trailed her human fingers over the wall of your quarters — over the cool filigreed archway, over the polished metal panels and inlaid bone — and said, “Well, I tried, and therefore no-one should criticize me,” before ducking through the arch to the foyer beyond. You heard the door shut behind her. You were left profoundly alone.

The heat rose. The station must have been completely smothered: wrapped in a squirming shroud of thorax and wing, mandible and antenna, the dead couriers of a hungry stellar revenant. Your communicator crackled with static, but there was only silence at the other end. There was silence in the lovely passageways of the Mithraeum, and there was a hot and sweating silence in her soul. When you screamed, you screamed without sound, your throat muscles gulping mutely.

You thought about the flimsy envelope addressed to you that read, To open in case of your imminent death.

“They’re breaching,” said the Emperor. “Forgive me… and give it hell, children.”

Somewhere far-off on the station there was a warping crunch of plex and metal. Your knees became jelly, and you would have collapsed to the floor in a spasm had you not been sitting. With your fingers you closed your eyes, and you wrestled yourself into stillness. The darkness got darker and cooler as the first shield of perpetual bone cocooned you — the act of a fool, meaningless, doomed to dissolve the moment you submerged — then the second, then the third, until you were lost in an airless and impregnable nest. Throughout the Mithraeum, five pairs of eyes closed in concert, one of them yours. Unlike theirs, yours would not open again. In half an hour, no matter what Teacher might hope, you would be dead. The Lyctors of the Resurrecting Emperor began their long wade into the River to where the Resurrection Beast squatted — just out of the orbit of the Mithraeum, half-alive, half-dead, a verminous liminal mass — and you waded with them, but your meat you left vulnerably behind.

“I pray the tomb is shut forever,” you heard yourself saying aloud, and you could not bring your voice above a choked whisper. “I pray the rock is never rolled away. I pray that which was buried remains buried, insensate, in perpetual rest with closed eye and stilled brain. I pray it lives… O corse of the Locked Tomb,” you extemporised wildly. “Beloved dead, hear your handmaiden. I loved you with my whole rotten, contemptible heart — I loved you to the exclusion of aught else — let me live long enough to die at your feet.”

Then you went under to make war on Hell.

***

Hell spat you back out. Fair enough.

You did not wake up having passed into the thanergetic space that was the sole province of the dead, and the necromantic saints who fought the dead; you woke up in the corridor outside your rooms, on your side and broiling, gasping for air, soaked right through with sweat — your own — and blood — your own; the blade of your rapier leered through your stomach, punctured through from behind. The wound was not a hallucination or a dream: the blood was wet, and the pain was terrible. Your vision was already curling up black at the edges as you tried to close the rent — tried to sew your viscera shut, cauterize vein, stabilize the organs whimpering into shutdown — but you were far too gone already. Even if you had wanted it, the Imminent death letter would not be yours to read. All you could do was lie gasping in a pool of your own fluids, too powerful to die quickly, too weak to save yourself. You were only half a Lyctor, and half a Lyctor was worse than not a Lyctor at all.

Outside the plex, the stars were blocked by the skittering, buzzing Heralds of the Resurrection Beast, beating their wings furiously to roast all inside. From very far away you thought you heard the ring of swords; that bright scream of striking metal which made you flinch every time you heard it. You had loathed that sound from birth.

You prepared to die with the Locked Tomb on your lips. But your idiot’s dying mouth rounded out three totally different syllables, and they were three syllables you did not even understand.

You can now pre-order Harrow the Ninth by Tasmyn Muir, out June 2, 2020.

Source: Read Full Article