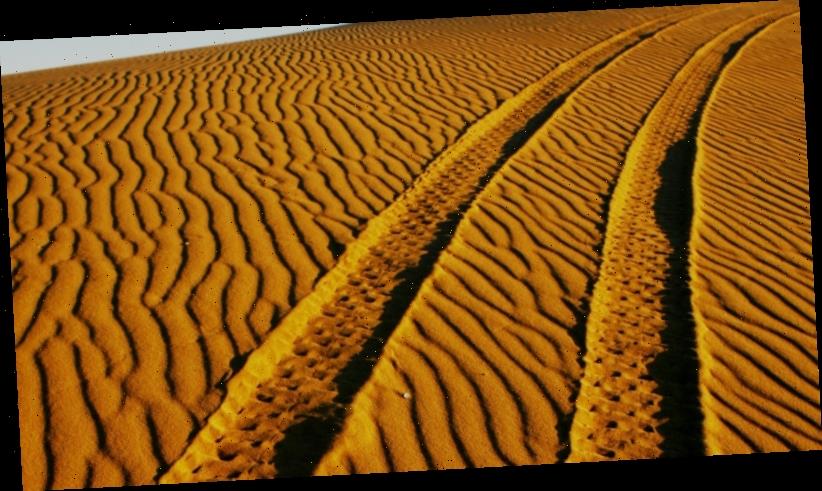

Our original trips were involuntary, our movement through the world, accidental.Credit:Darren Pateman

Before Ford went further and before Robert Johnson sang about the Greyhound bus. Before Lonely Planet travelled on a shoestring. Before Burke and Wills lugged a Chinese gong en route to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Before the Grand Tourists trekked through France and Italy in search of art and culture of the Western world. Before the exploratory routes of Cortés, Columbus, Magellan, Pizzaro, Cook, de Alvarado, de Narvaez, de Soto, and every other genocidal brute. Before the road trips that birthed civilisations and ages; exchanging languages and gods and goods across the Silk Road, the Spice Route, the Incense Route, the Amber Road and the Trans-Saharan Trade Route. Before 60,000 years, before our First Nations Australians traversed the relational maps, before the Songlines. Before it all – we were gliding on new continents across the seas, we were moving towards the ever appearing horizon of our futures.

The split of atoms, the shift of plates, that first migration – our original trips were involuntary, our movement through the world, accidental – weren’t we all born there? Aren’t we all the products of journeying and one day pausing? Isn’t all civilisation hinged on the eternal decision of where to set up camp?

This winter, on a road trip to nowhere in particular, we faced that age-old dilemma – upstream or downwind, north facing or nearer to the road? If you happened upon us – myself, my daughter and her best friend – you would have seen that we pitched in a more remote piece of earth below the arch of a Kakadu plum. The next night we moved the tent closer to a couple of other tents in the shape of safety in numbers.

I took the girls (inseparable, joyous, technology-addicted, stroppy teenagers) on the road trip of a lifetime: two months around Australia, camping and sightseeing between book events. From Melbourne to Byron, Sydney to Canberra, we looped the country for the first month and then, from Cairns to Darwin, we camped.

The first night the girls clumsily put up the tent and we crouched and ate baked beans and noodles very quietly. At first darkness fell like a great shock, a blanket dropping over the waning sun in the trees. All that first night I lay awake to the sounds of the snap of branches nearby. I had become too anchored and fearful as an adult; there was a gulf between my teenage and adult self too.

Ordinarily we live in France, where the camping culture is slim to non-existent. Camping seems to be code for the assembly of motorhomes and tents huddled in privately owned caravan parks replete with onsite restaurants. We live outside the city. The girls traipse outdoors, but there is less adventure in the French countryside – they don’t have to shake their boots for redbacks or scan their backyards for brown snakes. The Australian teenager I once was and the French teenager I’d raised had a great gulf between them – as wide as the water separating borders. When my daughter became a teenager I scrambled – I wanted her to learn how to make a fire, set up a tent, compartmentalise necessities, be equally cautious and curious of her homeland, to go without the internet for a while and to navigate with a paper map and feel confident she could do all those things and carry the skills into adulthood.

The Milky Way over outback Queensland.Credit:David Porter

I only slowly remembered what to do again: remembered the side of the road to drive on in the day, and how we needed to prepare for the night, remembered we were upside down and relying on the sun. Only after hovering my ear above the red dirt and blowing gently into the fire I’d just made did I smell all my life, all my most potent memories, return.

I’d done this before, thousands of times; all my youth was spent chasing elsewhere, crisscrossed by bitumen, tripping the world. The horizon was the promise of a mirage, the promise of nothing but change and everything but salvation. The road is stitched from head to toe deep inside me, that line across the land – it could always lead to a place holding an atonement for something vague, something shameful I’d done that I could never quite remember. I was never rooted. I’d hitchhiked for years, getting into cars with dangerous men. Sleeping in a tent in the middle of nowhere, alone, 17 years old. I was saving money to go again. To go and go and go on seeking some outer world where I imagined the adult me awaited my arrival, with open arms. I don’t run anymore. I’ve forgotten what I was looking for, or meant to be prostrating about.

In order to survive or grow, one must move.Credit:Michele Mossop

It’s part of the psychic inheritance that I’ve been handed – that in order to survive or grow, one must move. I don’t think I’ve passed it onto my daughter, even though we travelled from place to place, country to country until she was six years old. Her memory is instead soldered into our house, into the place we’ve stayed for longer than the road. In that village and street and yard and the home and the garden.

The garden is the antithesis of the road. There is a promise made when the seed is covered over, a commitment to staying the seasons, to seeing through the frost and fairer weather. To de-head in the winter, to mulch and nourish and to water each day. We identify stability with serenity – with being restful – and for some people it’s true. It was true for me. I think it’s true for my daughter too.

I remember the journeys when we were kids, up and down the coast, out by the river, near farming land, crouching round the fire pit, swimming in the deep. I remember taking the front seat instead of my brothers. I remember the glee that would, later in life, calcify in my bones as guilt.

I remember the surfing trips with my first love, first kiss, first time the car breaks down, first fight. Our best teenage plans laid waste. I remember being pulled over at the shoulder, changing the wheel; I remember the cassette tapes strewn, the windows down to cool off, tanning our forearms.

Our road-trip had a degree of self-mastery: hiring a car and returning it, being wild and surviving it, learning something to carry. It was a statement of confidence to my daughter: that she could move without having to. That you can run and return home.

On the road there were landslides of laughter, our bodies and the air between us split open, crackling with knowing one another better. I revisited grunge and punk rock playlists, the girls learnt to hand-wash their clothes and cook at the campfire. We hiked, learnt about our ancient cultures, and crossed rivers filled with crocodiles; we split coconuts on a beach below the migration of butterflies, we took home battle scars, small souvenirs. The trip wasn’t only to allow the girls to learn self-sufficiency, about history, about camping skills, but also – for my daughter – I was showing her a new inheritance of being able to go and always have a place to return to. I kept reminding them: you’re lucky, so lucky, so privileged. And as we travelled the country, as they returned home, I think they knew it.

Before we left the country, I drove down the other roads, the ones I used to live on, the places that the mind retreats to as we are hurtling towards a destination. The places where the past lives. The old houses that we are somehow tenants of forever. I visited if only to say goodbye to the other yard, another house, untended garden.

Back home I’m eternally turning – the soil now, the compost, and not the world. I don’t have itchy feet anymore, nor a reluctant heart. I don’t think I’ve found myself at the destination, or on the road, but I have brought myself along. I’ve steered myself into harbour. I’ve set up camp.

Source: Read Full Article