For kids today, the back-to-school season means buying school supplies, seeing friends again, meeting new teachers, learning new subjects, general back-to-school nerves … and lockdown drills. Just this year in the United States, as reported by ABC News, there have been 421 mass shootings. According to data from The Washington Post, more than 356,000 students have been exposed to gun violence at school. Lockdown drills started in 1999 after the Columbine School shooting. Since then, there have been 386 school shootings. Lockdown drills are, unfortunately, a necessary part of everyday school life. But are these drills really helping?

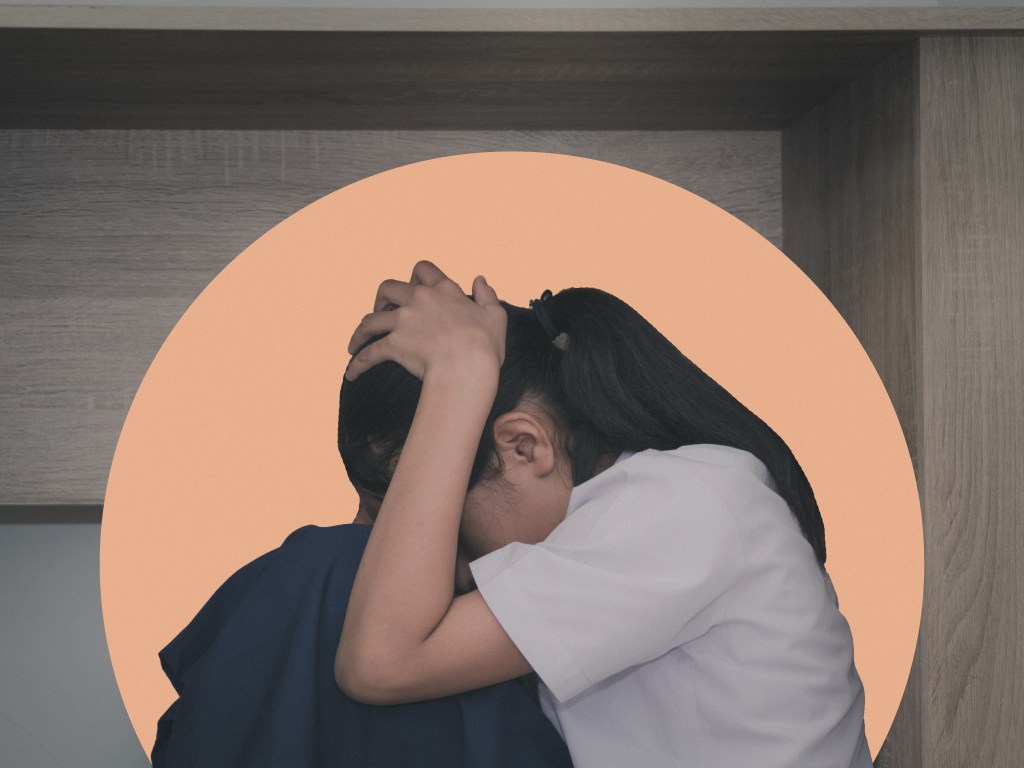

We asked a group of kids ages 11 to 18 to tell us exactly what these drills are like, how they make them feel, and what they believe needs to happen to prevent gun violence and increase gun safety in their schools and our country. Most of these kids did their first active shooter lockdown drill when they were as young as 7 years old.

“I’m kinda nervous when I do them, because they are practicing for something I really don’t want to happen.”

The methods for teaching kids how to respond to an active shooter varied widely. 14-year-old Naila says that at her school, students are told to go to a wall and face the windows. 18-year-old Reed reports that she and her classmates were taught about “improvisation and spreading out and getting away from the shooter versus staying in one place.” And according to 15-year-old Cameron, if a gunman entered their classroom, he and his peers were instructed to “hide behind a desk and throw things” — a measure he’s rightfully a little skeptical of, adding, “I don’t think anyone would do that. I feel like fear would kick in.”

“Presumably the shooter, if they’re a student, or somehow associated with the school, would also be learning all of these things [during lockdown drills] that we’re learning.”

Research has shown that gun violence — whether a child is directly affected by it or not — has a clear impact on kids’ mental health. For those who have been personally involved with incidents of gun violence, the aftereffects are long-lasting. 18-year-old Emma reveals she and her family were the victims of an armed gun robbery at her uncle’s home. “The first time I saw a gun was when I was 6 or 7 years old … Two men with guns came in and were robbing the house, and they were pointing guns at my mom, my aunt.” Years later, Emma confesses, “It definitely instilled a fear in me. And for the next 3 years, I couldn’t even sleep with the lights off, because I was so scared that in the dark, [I’d] turn around and someone with a gun would be behind [me].”

Even when kids have never been close to gun violence themselves, there’s still an impact. Pew Research Center found that a majority of teens say they’re worried about a shooting at their school, and clinical psychologists say that many of the young people they treat see gun violence as an ever-present threat and are constantly planning “escape routes” in case they find themselves in the middle of a mass shooting event. “These tragedies are happening far too often, and the result is that many young people are feeling this constant back-of-the-mind stress,” Erika Felix, PhD, of the University of California, Santa Barbara, said in the American Psychological Association’s Monitor on Psychology.

“I wish I could say lockdown drills make me feel safer in school, and more prepared, but they really don’t,” Emma admits. Cameron says his sense of safety in crowds is at an all-time low: “With the growing threat of someone just massacring everybody they see, it makes it a lot harder to feel safe in big public spaces. Because that’s just a scary thought.”

“With all the gun violence that’s been going on in the world, I feel like it’s going to happen eventually, and I might get caught up in it. And I don’t want that to happen.”

When asked what they thought could be done to reduce gun violence, most of the teens agreed access to guns is too easy and there are not enough restrictions. Some suggest stronger education on gun safety or more background checks. “Even if you’re over 21, there should be a test or class you have to take on gun safety, just in case something does happen,” said Naila, 14. Others said parents needed to lock up their guns at home.

“I do think teachers should be trained to deal with shooters. Not like using guns to protect themselves, but I mean like, knowing how to hide students,” Marques admits. Naila felt differently: “I think it’s pretty ridiculous that it should be even thought of as a teacher’s requirement, when their job is to teach students and to help them grow as a human.” Emma added, “I honestly don’t think teachers should be trained to fight off gunmen. I think we need to fix our society, not making teachers able to fight them, but to make the gunmen not want to come in.”

3963 children and teens die by guns per year; 33% of deaths among this group are suicides, 62% are homicides.

Simply put: Hi, it’s the guns. The guns are the problem. It’s them. And the only ones who can help are us — adults. Laws. Legislation. Parents. Politicians. And it’s going to take much more than thoughts and prayers. We all need to take action, because that’s the only way to help make schools safer … so our kids don’t have to crouch in a corner wondering if they will be the next news story.

For more information on actionable steps — small and large — that you can take to prevent gun violence, visit Everytown or Sandy Hook Promise.

Source: Read Full Article