Most hotels charge you to stay, but Hotel Influenza will not be like most hotels. Guests at this newly renovated, soon-to-open facility in St. Louis will check in for about ten days, at no charge, and stay in one of 24 private rooms, each equipped with desks, Wi-Fi, and a flat-screen TV. There will be a lounge, food, and even exercise facilities. And not only will all this hospitality be completely free, but the carefully chosen group of guests will actually get paid to stay there: Each will receive a check for about $3,000. All they’ll have to do is volunteer to get sick.

Or maybe not. Researchers from St. Louis University, one of nine federally funded Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units racing to find a universal flu vaccine, will most likely greet guests at what is technically called the Extended Stay Research Unit by administering a flu shot. Then they’ll give the lucky guinea pigs a new experimental flu vaccine, give the unlucky ones a placebo, and then stick flu virus up their nostrils. Over the next ten days, the guests will be monitored for all manner of flu-like symptoms, every runny nose or sleepless night a measure of the vaccine’s effectiveness. Some of them will likely feel fine at checkout. Some will probably feel like hell.

The researchers are there to figure out who gets sick and why, says Daniel Hoft, M.D., Ph.D., director of the university’s Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology. Dr. Hoft is one of the architects of the Hotel Influenza research, and the facility will enable his team to do human challenge studies with a smaller number of volunteers and at less cost than traditional vaccine experiments.

“In a traditional flu study, we vaccinate people and see if their immune systems respond by creating antibodies that fight flu,” wrote Dr. Hoft on the university’s website. “In a human challenge study, we vaccinate people, then deliberately challenge their bodies by exposing them to flu to see if they get sick.” Researchers plan to enroll volunteers in a study by the end of the year.

Getty ImagesKim Kulish

The reason for the research at Hotel Influenza is as intriguing as its name. For years, normally staid researchers have engaged in a venomous battle over how well flu shots actually work, if at all. In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the vaccine was anywhere from 22 to 100 percent effective (depending on the age group receiving it), and skeptics said that couldn’t possibly be true.

Now, a decade after scientists first demonstrated serious flaws in measures of vaccine effectiveness, the CDC acknowledges that vaccine protection isn’t all it’s been cracked up to be. Which, of course, most of us already know: Last season was among the worst flu seasons in memory, with flu shots working only one-third of the time and approximately 31 million people suffering through the aches and pains and sweat and chills of influenza.

The exact number of people who died from flu last season isn’t yet known, but since 2010 the number has ranged from 12,000 to 56,000 annually. The precise figures are uncertain, because states are required to report flu deaths only among children and because anyone who dies from complications of flu or a flu-like illness could be counted as a flu death.

What is certain is that the toll on individuals is huge: sick days and canceled plans and endless days of feeling lousy. And the broader economic implications are staggering: Medical expenses and lost wages from flu cost the United States $11.2 billion each year. Yet despite billions of dollars in public and private research and development, and dramatic increases in the rate of flu vaccination over the last 40 years, the number of flu deaths hasn’t declined nearly as much as might be expected. Why are flu shots so ineffective? And should we even bother getting one?

The shot that misses

Let’s start with the first question. A small part of why flu shots aren’t very effective is because experts have to formulate a new vaccine each year based on an educated guess. Every February, before the current flu season is over, public health officials and researchers around the world look at historical and contemporary epidemiological data to make their best prediction of which strains of flu will dominate in the coming season. Then, while the rest of us are spending our summer going to the beach, manufacturers race to produce the next batch of shots in time for early fall, when the CDC begins issuing warnings about flu season and urging Americans to get their shots. Flu shots are offered at doctors’ offices, hospitals, airports, pharmacies, schools, polling places, shopping malls, and big-box stores like Walmart. About half of all Americans get one, and the remaining 50 percent have their reasons for skipping. Some believe, mistakenly, that the vaccine causes flu. Others just don’t like needles.

In some years, public health researchers and vaccine makers get it right. Numerous studies over the years have claimed that the correct vaccine can be remarkably effective at reducing the risk of catching the flu and dying of it. But sometimes, like last year, they get it wrong: They produce a shot for three or four strains of flu only to be outwitted by a virus that has morphed to be slightly different and can evade the vaccine. There’s even a word that researchers use to describe the phenomenon: drift. And the hard part of this calculation is that researchers can’t predict drift.

The second question—whether we should even bother getting a shot—is the trickier one. Despite the fact that roughly half the population now gets vaccinated each year, flu seasons come and go with about the same number of cases and the same number of deaths as when virtually no one was vaccinated. In the past, public health officials assumed that this had to be the result of their failure to convince even more people to get a flu shot. Very few of those in public health were willing to raise the possibility that maybe the vaccine was the problem.

In 2005, Lisa Jackson, M.D., M.P.H., a physician and senior investigator with the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, began raising questions about a claim that the vaccine cut seasonal flu deaths among the elderly in half. (Her research has implications for younger people too, even though they’re less at risk.) She and several colleagues conducted a study of more than 72,000 people ages 65 and older and discovered that the sickest were less likely than healthier seniors to get the vaccine. They then examined the baseline rate of death for vaccinated and unvaccinated groups and found that the unvaccinated elderly were 60 percent more likely to die outside of flu season.

This suggested there was a phenomenon at work known as the “healthy-user effect,” in which cause and effect are confused when healthy people, who are less likely to die anyway, receive vaccines or drugs and their better outcomes are mistakenly ascribed to medical intervention rather than to their baseline better overall health. In other words, the frail elderly, often bedridden and near death, were unlikely to go to a doctor’s office for a flu shot, while healthy elders did get the shot. It wasn’t the vaccine that made the difference; it was the patient.

Around the same time, Lone Simonsen, Ph.D., then a re- searcher with the National Institutes of Health, led a group of investigators who looked at death rates from flu over time. They found that despite a significant increase in the number of elderly people being vaccinated (rising from 15 percent before 1980 to 65 percent in 2001), there was no corresponding decrease in the death rate among that group. Nor did they find an increase in deaths in years when the vaccine was known to be not well matched with circulating flu viruses.

Until very recently, Jackson, Simonsen, and other critics of the flu vaccine’s effectiveness expressed their opinions at the risk of ridicule and attacks from other public health experts and researchers. Jackson was told she was putting her career in jeopardy when she began her study. When she tried to publish her results, her papers were initially turned down by top journals, whose editors said the results were simply not credible.

The CDC now acknowledges that since 2004, flu vaccine efficacy has ranged from 10 to 60 percent. That’s not great.

The illusion of benefit

Overestimates of flu vaccines’ effectiveness are understandable, says Michael Osterholm, Ph.D., M.P.H., an infectious- disease expert and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy in Minneapolis. In the past, flu research has been littered with errors, not to mention a good deal of marketing by both manufacturers and public health officials hoping to sell people on the only defense available. And part of what misled everybody was the lack of an accurate test for flu.

There’s also the slow-to-die myth that flu shots actually cause the flu. Flu-like symptoms may be the result of a different virus, and the list of bugs that can make you feel like you have the flu is a long one. So when people got sick after receiving a flu shot, most officials assumed that one of those other viruses was to blame. That is, until 2007, when polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, a far more accurate test for detecting influenza infection, became more widely used. Researchers discovered they had seriously under- estimated the rate at which people actually came down with flu after being vaccinated. It wasn’t that the vaccine caused flu; it’s just that it was lousy at preventing it.

The CDC now acknowledges that since 2004, flu vaccine efficacy has ranged from 10 to 60 percent. That’s not great, and not comparable to the protection of many other vaccines, like smallpox and polio, which are between 91 and 100 percent effective. Still, even with efficacy of just 40 percent, such as during the 2016–17 flu season, the vaccination “prevented an estimated 5.29 million illnesses, 2.64 million medical visits, and 84,700 hospitalizations associated with influenza,” says the CDC.

It’s also worth noting that young children, pregnant women, and the elderly are especially at risk and may benefit more from the vaccine. There’s even evidence that a new, high-dose flu vaccine decreases the rate of pneumonia among the elderly from 7.4 events to 4.4 events for every 1,000 individuals vaccinated.

Despite its spotty effectiveness, flu-vaccine uptake continues to rise, and GSK, which manufactures a vaccine for anyone six months old and up, sold 40 million doses in the U.S. for the 2017–18 flu season. Last year’s sales jumped by 12 percent, pulling in $677 million for the pharmaceutical giant. And though some companies stopped producing flu vaccine due to low profit margins (much more can be made on drugs and medical devices), in recent years a massive influx of money from private and government entities has changed things. GSK won’t reveal its profit margin on flu vaccines but told Men’s Health that it’s “just below the profit margins of Rx [prescription drugs] and with a built-in advantage of no patent cliffs.” Patents can last more than 20 years, and since vaccines have to be reformulated every year, there are no generic products to undermine a manufacturer’s profits.

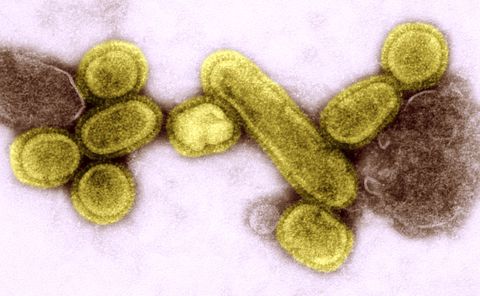

Researchers are working in tandem with BiondVax, GSK, and a handful of other pharmaceutical and biotech companies in the race to develop a universal flu vaccine—one that would target “conserved,” or stable, parts of the virus’s DNA, potentially providing protection against all flu strains, even as they drift, and lasting for years. Such a vaccine would trigger the immune system to be prepared to defend against any version of flu virus—and even protect against the kind of pandemic that could be a global disaster of unimaginable proportions.

Such a vaccine is a holy grail for public health. It’s also a moon shot. Other viruses have eluded all efforts to produce an effective vaccine, including HIV and the common cold.

Ironically, the huge financial incentives to create such a vaccine may complicate things further. The flu-vaccine market is expected to reach nearly $3 billion by 2024. The market for a universal vaccine promises to be substantial. With billions of dollars at stake, drug and biotech companies have shown in the past a certain willingness to cut corners and exaggerate results. Even the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not been particularly effective at curbing the hype and the distortion of science associated with many drugs having even less financial potential.

A new (old) threat

While flu is no picnic for anybody who gets a bad case of it, seasonal influenza outbreaks are not what worry public health officials the most. During his more than three decades as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci, M.D., has overseen the national research effort for some of the worst epidemics of the last century. He was there as AIDS was heating up and when West Nile broke out, and he has supervised the vaccine effort to combat Ebola. But when asked what keeps him awake at night, Dr. Fauci answers quickly: “Pandemic influenza.”

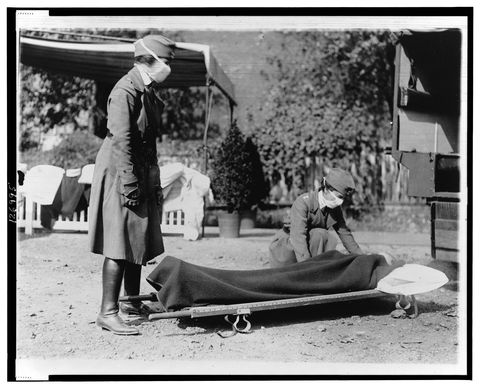

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines “pandemic” as any international outbreak affecting a large number of people. The deadliest pandemic in recorded history was the 1918 “Spanish flu,” which killed an estimated 50 million to 100 million people around the world. That’s more than the number felled by plague in 14th- century Europe or during battle in World War II. Despite a century of study since the 1918 pandemic, mysteries remain. Investigators argue about whether the enormous number of deaths was the result of an unusually powerful strain of flu virus or something else that was happening at the same time.

Peter Doshi, Ph.D., now an assistant professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, was a graduate student at MIT when he became intrigued by the assumption that novel flu viruses, the cause of pandemics, were intrinsically more deadly. In order to examine the question, he studied historical records of flu deaths, all the way back to 1905, and created a graph of deaths over time. The image is startling.

“What you can see clearly is that deaths began to dramatically decline long before influenza vaccines were introduced and widely used,” he says.“Influenza is simply not the threat today that it was many decades ago.” Doshi predicted in a 2008 paper in the American Journal of Public Health that if trends continued, the next pandemic would not be catastrophic. He was to be proved correct the very next year, a pandemic year for H1N1 “swine flu,” which turned out to be, he says, “the world’s most mild pandemic ever.”

“Another 1918-type pandemic is in the world’s future, and this one could be even more deadly.”

Another point of disagreement for flu researchers is how outbreaks of the 1918 flu occurred among individuals or groups that were apparently unconnected. To find the answer, Tom Jefferson, a researcher with Cochrane Collaboration, dove into real-time reports published in the British Medical Journal during the pandemic. Jefferson’s search led him to his “mushroom theory.” He thinks something more than the virus’s virulence—how inherently deadly a particular strain of virus is and how readily it spreads—was at play in 1918, and that something was the underlying health of large populations around the world.

During the last months of World War I, people across the globe were suffering. In Europe, a sizable percentage were living in bombed-out cities, hungry, dirty, and crowded together in unsanitary conditions. Troops coming home to the U. S. were exhausted and crammed into trains. Like mushroom spores that sprout only when conditions are right, a nasty strain of flu virus found fertile ground in a weakened populace. Jefferson’s argument is that the death rates of recent pandemics haven’t come close mostly because of advances in public sanitation, reductions in crowding, and better nutrition and wellness.

However, many other experts don’t buy Jefferson’s mushroom theory. Osterholm, for one, says viral virulence played a central role in the massive death rate seen during the 1918 pandemic. He believes another 1918-type pandemic is in the world’s future, and this one could be even more deadly. For one thing, the world’s population is bigger.

But the other reason may surprise you. Osterholm thinks a superpandemic is more likely now because of poultry. Large-scale industrial farms are a breeding ground for new flu strains. Birds, confined in cages stacked on top of one another, drop waste on birds below, passing flu viruses from bird to bird that combine and mutate in what Osterholm calls a “genetic roulette wheel” that’s spinning faster and faster.

Factory farming, in which pigs and birds are crowded into enclosed spaces, replicates some of the conditions of 1918, speeding the transmission of viruses from animal to animal and to the hundreds of millions of humans who work with or live in close proximity to farm animals. This, says Osterholm, increases by orders of magnitude the possibility that new, and potentially more lethal, viral mutations will emerge.

It’s a stark reminder of why the quest for a universal vaccine and the research at Hotel Influenza is so critical. Dr. Hoft and his colleagues at St. Louis University may eventually make breakthroughs in the search for protection against all flu strains—including pandemic influenza. For now, the rest of us are stuck with a technology that works, at best, only half the time. But ultimately, says Osterholm, “some protection is better than none.”

Despite the billions spent on research and the divergent views about flu, one thing researchers all agree on is a low-tech strategy. During flu season, wash your hands for 20 seconds with soap and water multiple times per day, especially after you touch something handled by others. The flu virus can survive on surfaces like doorknobs for up to 48 hours. It is a fiercely resilient foe.

A version of this article appeared in the October issue of Men’s Health Magazine.

Source: Read Full Article