Inspired by her transgender son and faith that evolving science may help transgender women have their own children one day, 49-year-old mother Silvia Park from Charlottesville, Virginia, shares what it was like to donate her uterus as part of an ongoing clinical trial this past spring.

I was driving with my 16-year-old in the passenger seat about five years ago when he said, “I’m a boy.” The declaration was news to me—I was so shocked that initially, I didn’t know what to say. At the same time, I had no doubt my husband and I would support him as a transgender man—a person who transitions from a female birth assignment.

In the days that followed, I got involved with a PFLAG (Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) support group to learn how to be there for him. Now that my son is 21, I try to stay on top of medical advancements that could improve the quality of life for all trans people.

In December 2017, I saw an article about a woman who’d received a uterus transplant from a live donor as part of an ongoing Baylor University Medical Center clinical trial working toward a new infertility treatment option for women who are cisgender—aka, not transgender—with nonfunctioning or nonexistent uteruses. My mind wandered from this particular woman, who later got pregnant and delivered a baby without complications. One day, I thought, maybe this kind of procedure could help transgender women—people who transition from a male birth assignment—carry their own children.

The potential excited me, despite ethical issues that make this new science, which has helped two patients conceive so far, controversial: Unlike other organ transplants that involve live donors, this one only improves, rather than saves, the recipient’s life—while introducing substantial risks for both parties. What’s more, transplant patients have to take anti-organ rejection drugs that may cause side effects, ranging from tremors and hair loss to high blood pressure and diabetes, for as long as they have the organ. The medications suppress the immune system and increase the risk of infection and cancer, so they ultimately have to have the organ removed during childbirth or in a separate surgery after having kids. This opens the door for even more risks and potential complications.

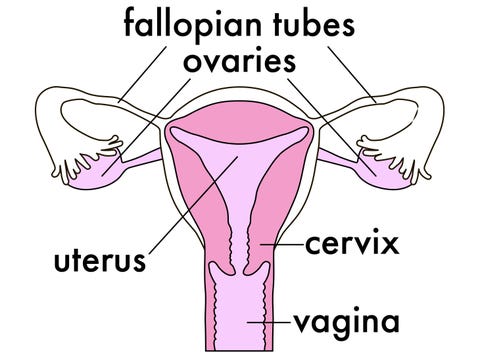

Pregnancy in Uterus Transplant Recipients

• In clinical trials, doctors are transplanting uteruses from live or deceased donors to patients who’d like to bear children but don’t have a functioning uterus.

• Recipients undergo in vitro fertilization to harvest their eggs prior to surgery.

• As soon as 12 months after surgery, artificial insemination can lead to pregnancy and childbirth via C-section.

• To date, one uterus transplant recipient in Sweden and one in the U.S. have had children.

• All recipients require full hysterectomies after pregnancy, either during a C-section birth or in a separate surgery, to avoid ongoing risks.

But as a mother of two biological children and one stepchild, I’ve always believed that everyone should have the right to decide whether they want to carry a child, regardless of their gender. And I desperately wanted to contribute to the cause.

I work in the medical industry as a medical coder and biller, but because I’m not a doctor or researcher, initially, I felt helpless. And then it dawned on me: I’ve already had two children and have no plans to carry another. I could donate my uterus. Although it wouldn’t go to a trans woman who wanted to have a baby, my donation could help doctors learn more about the procedure, and, I hoped, lead to another clinical trial that would give trans women the ability to conceive. Although it wouldn’t help my son directly—as a transgender man, he has a uterus, and probably won’t want to carry a child, anyway—it was something I could do now to potentially help the trans community of the future.

How Uterus Donation Works

Although I’d never even donated blood, I kept thinking about the trial as the holidays came and passed. In the new year, I spoke with a Baylor staff member on the phone to learn more about the procedure, which is similar to typical hysterectomy and performed with extra care to protect the organs during removal.

Although the procedure doesn’t affect monthly hormone fluctuations, it does stop menstrual bleeding, since without a uterus, there’s no lining to shed. The ovaries continue to function normally, except eggs don’t migrate as they mature—they remain in the ovaries. Although this means you never can get pregnant again, at age 49, I had no desire for more children.

“I had no desire for more children.”

I did have concerns about post-operative pain and what the scar would look like when it healed. But having never had surgery before, I had no negative experiences to draw on. Mostly, I was excited by the potential of being a part of such new science. And although I never asked Baylor whether they were planning to include transgender women in future clinical trials, in the back of my mind, I hoped they would.

Because I’d had two full-term deliveries and no serious health issues, I appeared to be eligible to participate in the trial. The next step, I learned, would be flying to Baylor in Dallas, Texas, for two days of screenings. There, they’d test my veins, arteries, and blood to make sure I was healthy enough to undergo surgery and provide a viable organ.

Initially, anxiety deterred me: I’d always had a fear of needles and I don’t do well with the sight of my own blood. And yet? I knew I was in a position to do something good, and I wanted to go through with it—not just talk about it. So, in February, I took two days off work to fly to Dallas. Because federal law prohibits the sale of human organs, and footing the bill on my transportation could be construed as breaking the law, Baylor only could cover my medical expenses and post-transplant housing on the hospital’s campus. To raise money for out-of-pocket costs, I started a GoFundMe page and began using it to document my journey.

When I got to the hospital, I was poked, probed, and scanned. Gritting my teeth, I gave several vials of blood. I also met with three surgeons and a psychologist to assess my mental stability: The doctor wanted to know whether I had support at home and whether my choice to donate an organ would lead to psychological issues later on.

During our conversation, I answered questions about my motivation and how I thought I’d respond to different surgery outcomes. But because I knew I’d be going into the procedure healthy and willingly, I was confident that I’d come out of it perfectly fine.

When I was approved as a donor several weeks after that first trip, everything felt more real. But the news didn’t scare me off; it left me feeling even more committed. Not once did I consider changing my mind—not even after I was matched with a recipient and scheduled for a March surgery, only to have that patient reassigned to a different donor who was a better match, which, I was told, is determined by blood type and each patients’ specific immune system antibodies.

When Baylor found a second match for me soon after, we set a spring surgery date, and I began to spread the news that I’d be donating my uterus.

My friends asked lots of questions—they’d never heard of someone donating this particular organ. Initially, family and friends were worried—after all, this kind of surgery seems scary, and I was opting into it electively. Meanwhile, I felt like it was such a small thing for me to do. I had absolutely no use for my uterus. People who give a kidney—that’s really amazing.

“I felt like it was such a small thing for me to do. I had absolutely no use for my uterus.”

Ultimately, everyone was really supportive, and no one tried to talk me out of it. Although my son plays his cards close to his vest, and we didn’t talk about it much, I was moved when he and his friends shared my GoFundMe campaign on Facebook.

Even my boss was encouraging: She told me to go for it, even though I’d have to go on medical leave, meaning I’d miss work and receive just 70 percent of my income during the three-week recovery period I’d have to spend in Dallas after surgery.

In a pre-operative call with a Baylor nurse before my procedure, my husband, who, unlike me, had undergone surgery before, helped me ask the right questions to understand the typical risks, like infection or bleeding that requires a blood transfusion, and general anesthesia, which runs a low risk of death. But I trusted my medical team.

When I flew down with my husband for my surgery this spring, I was more nervous about the flight than the procedure I was opting into. Thinking about it didn’t stir up anxiety—it just got me excited.

My abdomen was swollen when I woke up after surgery. I felt sharp pains emanating from within and a burning sensation as if my core muscles were being stretched. It was especially bad when I sneezed, which would cause brief bouts of excruciating agony. My right leg, I noticed, felt numb, although my doctors explained this stemmed from nerve inflammation due to my positioning on the operating table.

My surgery, which lasted eight hours, took longer than expected. When working with live donors, my nurses explained, particularly in clinical trials featuring new procedures, surgeons take extra precautions to make sure they do no harm to the patient or to the organ they’re removing.

The day after my surgery, I took a tentative step out of bed when I felt my right knee give way. Having run a half marathon just two weeks before flying to Dallas, the weakness weirded me out, but my medical team stayed calm, reassuring me there was no permanent damage.

As expected, my numbness went away after a few days. I had no other complications — everything went fine, I was told. Although I’d hoped to avoid narcotics, since I was told they could slow healing, I used a morphine pump during those first few days along with another narcotic. Although my abdomen was still swollen by the third day, lying still caused no pain, so I was able to switch to an over-the-counter painkiller.

Ultimately, I was so focused on my own recovery that I didn’t really think about meeting the woman who’d received my uterus in the very same hospital right after my hysterectomy.

If she had asked to meet me, I would have done it for sure. But as it happened, she didn’t. No one told me anything about her, not even her exact age, for privacy purposes.

In hindsight, I can see why people don’t tend to volunteer for surgery. I mean, I went into it super fit, and recovery still took quite a toll on my body—I can’t imagine what it must be like for people who go in when they’re sick.

After five days in the hospital, I was discharged and moved into accommodations designed for out-of-state donors to recover before traveling home. Because my doctors discouraged me from staying by myself, when my husband left to go back to work, my younger son, who is 18, flew out to stay with me. I couldn’t have done it without either of them.

“I can see why people don’t tend to volunteer for surgery.”

Throughout my two-week stay, the intermittent pain I’d been feeling lessened every day. Although I was mostly resting with short walking breaks, I felt incredibly worn out and tired all the time. It was a good thing I wasn’t allowed to lift anything heavier than 10 pounds, since I don’t think I had it in me.

Toward the end of my stay in Texas, I felt well enough to venture out with to a museum with my son. But I had to stop and catch my breath in the midst of climbing a single flight of stairs.

Now that more than a month has passed since my surgery, I’m feeling a lot stronger — strong enough to run a few charity races this summer and fall. Although the surgery slowed me down, and I’ll be sticking with 5Ks and 10Ks at first, maybe, in November, I’ll run another half marathon.

As I move on with my life, the organ that made me a mother may soon give another woman a chance to experience the same kind of joy parenthood has given me. Thinking of my uterus carrying someone else’s baby doesn’t strike me as weird. I no longer had a need for the body part. Now, it’s being put to better use.

I still haven’t spoken to my transgender son about the trial very much. At the end of the day, I don’t need him to tell me he’s proud of what I did. I like to think I would have done the same thing if I didn’t have a transgender child.

At the time of publication, Silvia has $1,540 of her $2,500 GoFundMe goal, which will cover the travel expenses Baylor wasn’t legally permitted to fund. If she surpasses her target, she’ll donate all additional money to Side By Side, a Virginia-based nonprofit organization dedicated to creating supportive communities for LGBTQ+ youth.

Source: Read Full Article