Has dead, 600lbs NASA satellite crashed in Africa? Hunt for spacecraft the size of a shipping container amid fears it may have landed in Chad overnight

- US space agency yet to reveal whether satellite burnt up or where it came down

- The 600-pound craft, about the size of a shipping container, was retired in 2018

A dead NASA spacecraft with a one in 2,500 chance of killing someone re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere overnight — but the US space agency is yet to reveal whether it burnt up or where it came down.

The 600-pound craft – about the size of a shipping container – was retired in 2018 after suffering a communication failure.

NASA refused to disclose its re-entry location but the satellite is thought to have come down between 00:50 BST and 02:50 BST this morning (19:50 ET and 21:50 ET yesterday).

Satellite tracking data suggests it may have crashed in Chad, Libya or Sudan, but this is yet to be verified.

Aerospace, a national security space program, previously revealed that the debris could fall anywhere in South America, Africa or Asia.

A dead NASA spacecraft with a one in 2,500 chance of killing someone re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere overnight — but the US space agency is yet to reveal whether it burnt up or where it came down

Satellite tracking data suggests it may have crashed in Chad, Libya or Sudan (pictured)

A mysterious flash that lit up the skies over the Ukrainian capital Kyiv generated much speculation that this might have been the dead spacecraft, but NASA dismissed this.

READ MORE: Moment one of Elon’s new Starlink satellites falls from the sky and burns up

One of Elon Musk’s new Starlink internet satellites deorbited this month, fells toward Earth and burned up in the atmosphere.

US space agency officials said the satellite was still in orbit at the time of the flash.

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer and astrophysicist at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told DailyMail.com the object ‘definitely was not’ the NASA satellite nor space debris.

‘[It could be a natural meteor or Russian missile attack,’ he said.

Experts previously said there was a 75 per cent chance that debris from the dead satellite would crash into the ocean, but NASA did acknowledge there was a ‘low’ risk of it impacting land.

Professor Hugh Lewis, who teaches astronautics at the UK’s University of Southampton, shared on Twitter: ‘Unfortunately, many people live within the latitude region, which means that the chance of a casualty is still relatively high.’

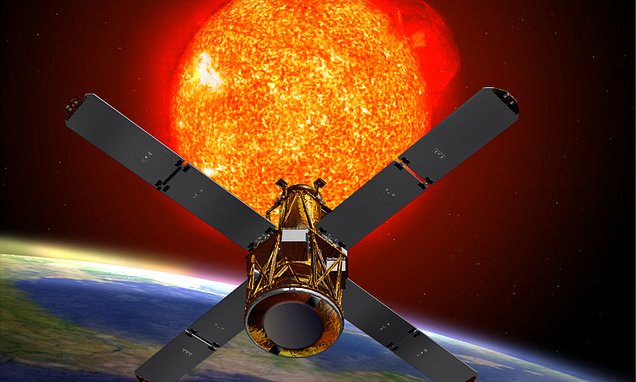

The dead craft is NASA’s Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), which was tasked with observing solar flares when it launched on February 5, 2002.

It was decommissioned in 2018 after NASA failed to communicate with it.

RHESSI launched aboard an Orbital Sciences Corporation Pegasus XL rocket, aiming to image the high-energy electrons that carry a large part of the energy released in solar flares.

It achieved this with its sole instrument, an imaging spectrometer, which recorded X-rays and gamma rays from the Sun.

Before RHESSI, no gamma-ray or high-energy X-ray images of solar flares had been taken.

Where the satellite could have crashed: NASA refused to disclose its re-entry location but the satellite is thought to have come down between 00:50 BST and 02:50 BST this morning (19:50 ET and 21:50 ET yesterday)

A mysterious flash that lit up the skies over the Ukrainian capital Kyiv generated much speculation that this might have been the dead spacecraft, but NASA dismissed this

Data from RHESSI provided vital clues about solar flares and their associated coronal mass ejections.

These events release the energy equivalent of billions of megatons of TNT into the solar atmosphere within minutes and can have effects on Earth, including the disruption of electrical systems. Understanding them has proven challenging.

RHESSI recorded more than 100,000 X-ray events during its mission tenure, allowing scientists to study the energetic particles in solar flares.

The imager helped researchers determine the particles’ frequency, location, and movement, which allowed them to understand where the particles were being accelerated.

Source: Read Full Article