Earlier this week, I got attacked by penguins.

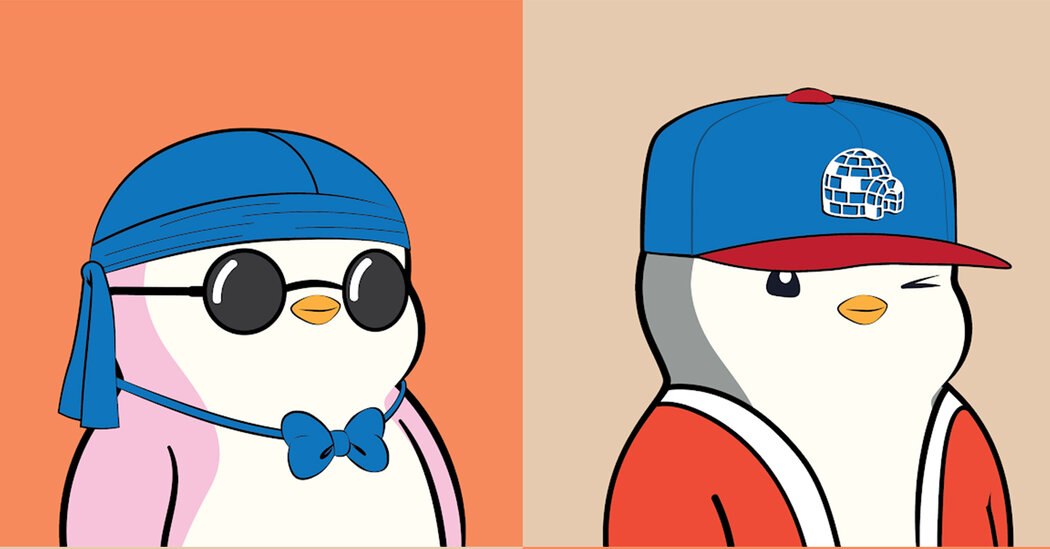

Not real ones, mind you. These were Pudgy Penguins — a flock of Twitter accounts with cartoon penguins as their avatars, which descended on me with messages like “Welcome to club pengu!” and “Enjoy the huddle!” As the replies flooded past, I saw penguins with sunglasses and penguins wearing sombreros, penguins with bow ties and penguins with mohawks. Dozens of penguins became hundreds; soon, my mentions were overflowing with bulbous and beaked interlopers, all congratulating me on joining them.

What had I done to deserve this welcome wagon? Well, a few minutes earlier, I’d acquired my very own Pudgy Penguins, marking me as an owner of one of the internet’s strangest new status symbols.

For months now, the crypto-obsessed have been buzzing about the rise of “community NFTs,” or nonfungible tokens, a kind of digital collectible that combines the get-rich-quick appeal of cryptocurrency with the exclusivity of a country club membership.

If you know anything about NFTs, you probably know that they are one-of-a-kind digital objects — cryptographic tokens, hosted on the Ethereum blockchain, that correspond to a digital asset, such as an N.B.A. highlight video or a piece of digital art. The most valuable NFTs — including the column I sold as an NFT this year for more than $500,000 — attract buyers for the same reason that Renaissance paintings do: because only one of them exists.

Community NFTs, by contrast, are group projects. They’re released in sets of unique but thematically linked images that can be bought and sold individually. Buying a community NFT typically entitles you to certain benefits, including membership in a shared Discord server or access to a private Telegram channel, where you can talk with other owners. (The biggest perk, though, is getting to change your Twitter profile photo to your NFT, marking yourself as part of the in crowd.)

I decided to join the Pudgy Penguins because … well, it’s August and I’m bored. But I also wanted to explore a more serious undercurrent. For years, technologists have been predicting the rise of the “metaverse,” an all-encompassing digital world that will eventually have its own forms of identity, community and governance. Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Facebook, recently said the social network would pivot to becoming a “metaverse company.” Epic Games, the maker of Fortnite, has also bet big on the metaverse, raising $1 billion to build its own version of digital reality.

Metaverse enthusiasts believe that our digital identities will eventually become just as meaningful as our offline selves, and that we’ll spend our money accordingly. Instead of putting art on the walls of our homes, they predict, we’ll put NFTs in our virtual Zoom backgrounds. Instead of buying new clothes, we’ll splurge on premium skins for our V.R. avatars.

Pudgy Penguins, and similar NFT projects, are a bet on this digitized future.

“The way I describe it to my family members and friends is like, people buy Supreme clothes, or they buy a Rolex,” Clayton Patterson, 23, one of the founders of Pudgy Penguins, told me in an interview. “There are all these ways to tell everyone that you’re wealthy. But a lot of those things can actually be faked. And with an NFT, you can’t fake it.”

Mr. Patterson, who goes by the online handle “mrtubby,” is a computer science student at the University of Central Florida. He started Pudgy Penguins with three classmates this summer after seeing other community NFTs take off. They chose penguins as their theme because the birds seemed approachable and friendly, and settled on using an algorithm to generate 8,888 unique penguins with different combinations of clothing, facial expressions and accessories.

“There was huge meme potential in fat-looking penguins, so we decided to roll with that,” Mr. Patterson said.

The first community NFT was the CryptoPunks, a series of 10,000 pixelated characters that was sold starting in 2017. They became a luxury status symbol, with single images selling for millions of dollars, and paved the way for other community NFTs, including the Bored Ape Yacht Club, a group of 10,000 cartoon primates that now sell for upward of $45,000 apiece.

Mr. Patterson and his co-founders hope that Pudgy Penguins will end up joining the NFT pantheon. The original collection sold out within 20 minutes, and more than $25 million worth of them have changed hands overall, according to NFT Stats, a website that aggregates data on NFT sales. Early this week, it was still possible to score a penguin for a few thousand dollars, but penguins with rare features, such as different-colored backgrounds or gold medals around their necks, can go for much more. The most expensive was Pudgy Penguin #6873, which sold for $469,000.

I messaged Mr. Patterson on Tuesday, asking if he had any advice for getting my own Pudgy Penguin without breaking the bank. (The New York Times’s expense policy does not, sadly, cover JPEGs of birds.)

“Hold on, I might be able to do something,” he wrote back.

Minutes later, two Pudgy Penguins — #3166 and #5763 — appeared in my cryptocurrency wallet. One was an image of a penguin with a do-rag and sunglasses; the other was wearing a baseball hat with an igloo and what looked like a bomber jacket. They were a gift, Mr. Patterson said, in appreciation of my willingness to learn about the community. (Since I can’t ethically accept gifts, I’ll be sending my Pudgy Penguins back to Mr. Patterson after this column publishes.)

I then joined the Pudgy Penguin Discord server, where I was greeted by a throng of fellow owners who were excited to see me, not least because they thought getting attention from The Times would increase the value of their own penguins. (After I received my images, I got offers to buy them for thousands of dollars.) The co-founders of Pudgy Penguins earn a royalty every time a penguin is sold, but other owners stand to profit only if they can resell their penguins for more than they paid.

Like any good crypto-clique, Pudgy Penguin owners have developed their own language and customs. Penguins are “pengus.” Owners are “huddlers.” “Tufts” are a rare, valuable type of penguin with no head covering, while “floors” refer to cheaper and more common varieties.

Several Pudgy Penguin owners told me that while they hoped to turn a profit if the price of penguins kept rising, they mostly saw it as a social opportunity. Pudgy Penguins claims to have more than 4,000 individual owners, and its Discord server, which you don’t need to own a penguin to join, is a hyperactive flurry of penguin memes, celebrations of new purchases and strategizing about how to get crypto-celebrities to join the club. (The group scored a coup on Tuesday when Alexis Ohanian, one of the founders of Reddit, showed off his newly acquired Pudgy Penguin on Twitter.)

“The people in the community are great,” said Christopher Aumuller, 29, a Pudgy Penguins owner from Queens. “Everyone is pretty much just vibing and sharing penguin memes.”

Tiffany Zhong, a cryptocurrency entrepreneur and investor, said part of the penguins’ appeal was that other popular crypto tokens had gotten too expensive.

“The average consumer has been priced out of those projects,” she said. “And so people who are trying to get into this are like, what’s the next big project I can get into?”

To the uninitiated, Pudgy Penguins may seem fundamentally pointless, and in some ways, they are. But I wouldn’t bet against them for the same reason I wouldn’t bet against the continued appeal of blue check marks on Twitter or O.G. Instagram user names. Humans are status-seeking creatures, always looking for new ways to elevate ourselves above the pack. The first iteration of the internet tended to flatten status distinctions, or at least make them harder to pin down — “on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” went the proverb — but newer technologies, including NFTs, have allowed for more obvious kinds of signaling.

Packy McCormick, the author of the Not Boring newsletter, argued in a recent essay that community NFTs were behaving as a kind of social network because they gave people access to social standing and connection, as well as a potentially lucrative investment.

“Powerful things happen when you combine money, status and community,” Mr. McCormick wrote.

It’s true that the people who buy Pudgy Penguins or other community NFTs may end up losing tons of money if the fad passes. But it’s also true that, like the Redditors gleefully pushing up the price of GameStop and AMC, the fans of these projects don’t seem to mind the risk. (In fact, some days, NFT traders and meme-stock speculators seem to be the only people still having fun on the internet.)

And while I personally wouldn’t invest my retirement money in Pudgy Penguins, I find the most common objections to them fairly unconvincing.

Are NFTs bad for the environment? Arguably, yes. Running the Ethereum blockchain requires a lot of computing power and energy, and NFT trades certainly contribute to the overall carbon footprint of the network. But they’re still a tiny portion of the overall cryptocurrency market, and their environmental impact is a drop in the bucket compared with the hundreds of thousands of regular Bitcoin and Ethereum transactions that take place every day.

Are they a rich person’s plaything, a waste of money that could be better spent elsewhere? Sure, but the same could be said of sports cars and designer handbags.

Is there something morally indefensible about people buying and selling blockchain collectibles for many multiples of the median annual U.S. income? Probably, but at least they’re not hurting anyone. (Put it this way: One of the least harmful things I can imagine a young, mostly male group of extremely online people doing in their spare time is trading pictures of cartoon penguins.)

The worst you could say about community NFTs is that they’re encouraging people to overpay for what amount to digital bragging rights, and that suckers will inevitably end up holding the bag when the bubble pops. But I doubt many fans would be dissuaded by the argument.

I told Ms. Zhong, the crypto entrepreneur, that I was still confused by the appeal of Pudgy Penguins, which didn’t seem to do much besides attract attention.

“That’s half the point,” she responded. “No one knows what’s going on, but it’s a lot of fun.”

Source: Read Full Article