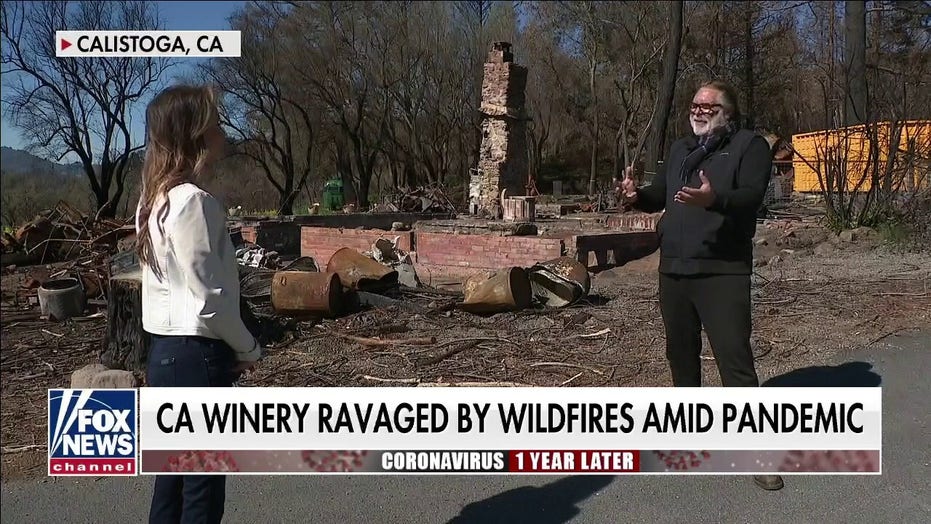

Business owner on overcoming wildfire damage amid coronavirus pandemic

Hourglass Winery owner Jeff Smith discusses his fight to rebuild with ‘Fox & Friends First’ co-host Jillian Mele.

Wildfires are burning in California. And Oregon. And Washington. And Arizona.

While fire is a restorative force that can ultimately revitalize ecosystems, it has been increasingly destructive and deadly in the West, fueled by extreme heat and persistent drought.

The scorched black shadows of trees still line the hills and mountains of the Golden State — a year-round reminder of looming danger.

The threat of wildfires to residents of the West is now seemingly omnipresent. It lingers long after the smoke has passed and the skies have turned crimson.

Homes are damaged in the blazes, memories go up in smoke and neighbors whose houses were miraculously untouched — just out of reach — are left to ponder the “what ifs?”

The deadly Napa and Sonoma counties wildfires in 2017 took a toll on the state’s important wine industry, with businesses still recovering from the financial wreckage years later.

The Bobcat Fire continues to burn through the Angeles National Forest in Los Angeles County, north of Azusa, California, September 17, 2020. (Photo by Kyle Grillot / AFP) (Photo by KYLE GRILLOT/AFP via Getty Images)

Last year, California saw the most acres burn in its most frightening and widespread wildfire season to date.

More than 4 million acres were charred in the Glass, Creek LNU and CZU Lightning Complex Fires, among many others.

Dozens of people were killed and almost 9,000 buildings were destroyed as firefighters from across the country, Canada, Australia and New Zealand worked to assist California’s federal firefighters in the effort.

Pacific Gas & Electric was forced to implement preventative rolling blackouts — impacting millions of customers — for the first time since 2001, citing record heat.

Wildfires in the state, meanwhile, ravaged the utility’s grid, cutting off a solar plant and transmission from a hydro plant.

PG&E, which had just emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy, was later made to pay $43.4 million in settlements with government agencies in three counties ransacked by wildfires ignited by its equipment in 2019 and 2020.

In Oregon, wildfires last year burned more than 1 million acres, nearly twice the average fire damage between 2010 and 2019.

And in Washington state, 2020 was the second-most devastating fire season in terms of acreage charred by flames.

The town of Malden in eastern Washington, home to around 200 people, was all but wiped off the map in September, as the state was ravaged by a “historic fire event” worsened by a Labor Day windstorm. More than 500,000 acres burned in less than 36 hours, and one person died.

Fire season dragged on through the end of the year and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data showed that 58,258 fires had burned 10,274,679 acres: the most acreage consumed in the U.S. since at least 2000.

The agency’s report of Selected Significant Climate Anomalies and Events across the nation showed that 2020’s wildfire season was the “most-active wildfire year on record across the West,” dating back to 1983, with three of the largest wildfires in Colorado history and five of the six biggest-ever blazes in California.

The nearly 10.3 million acres consumed exceeded the 2000 to 2010 average by 51%. NOAA noted that drought conditions had “expanded or intensified” across much of the West and southern to central High Plains throughout 2020 “with persistent above-average temperatures and precipitation deficits.”

In a recent report, scientists at NOAA and NASA announced they had determined that the planet’s atmosphere has been trapping an “unprecedented” amount of heat, with the planet’s energy imbalance approximately doubling from 2005 to 2019.

Increases in greenhouse gases emitted, such as carbon dioxide and methane, trap heat in the atmosphere and capture outgoing radiation. The increasing imbalance is also due to increases in water vapor and decreases in clouds and sea ice.

In its National Climate Assessment, NOAA wrote that the fact the Earth’s climate is changing is “apparent across the United States in a wide range of observations.”

“The global warming of the past 50 years is primarily due to human activities, predominantly the burning of fossil fuels,” the agency said, noting “stronger evidence confirms” that an increase in extreme weather and climate events are related to human activities.

With Mount Shasta in the background, a firefighter cools down hot spots on Monday, June 28, 2021, after the Lava Fire swept through the area north of Weed, Calif. (Scott Stoddard/Grants Pass Daily Courier via AP)

“Human-induced climate change is projected to continue, and it will accelerate significantly if global emissions of heat-trapping gases continue to increase,” said NOAA.

In looking at changes in heat waves, floods and droughts, NOAA researchers found that heat waves were occurring more often, as cold snaps decrease.

Over the month of June, multiple heat waves in the West set numerous records, with triple-digit temperatures in the normally temperate Pacific Northwest and northern Plains.

As sweltering and oppressive weather bared down on the region — killing hundreds in the U.S. and western Canada, many of whom were found alone in homes without air conditioning or fans — drought conditions worsened.

According to the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor report, more than 47% of the country is currently in some form of drought, with a shocking 93% of the West: the highest percentage for the region this century.

Almost 60% of the West is in either “extreme” or “exceptional” drought conditions, and it’s not expected to let up outside of an influx of moisture and precipitation across southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Buchanan Dam holds back water in Eastman Lake on Thursday, June 17, 2021, in unincorporated Madera County, Calif. At the time of this photo, the reservoir was at 11 percent of capacity and 20 percent of its historical average. (AP Photo/Noah Berger)

Some 1,500 critical reservoirs were shown to be worryingly dry in California and boat ramps were closed in New Mexico. State and local leaders issued emergency orders and declarations, hoping to receive federal assistance.

Cities in Utah banned fireworks ahead of July Fourth, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife was considering relocating some fish species, Idaho water managers cut off irrigation flows to farmers and Utah’s Republican Gov. Spencer Cox called on residents and businesses to use less water.

Dry vegetation was a harbinger of tough times months before sweeping action was taken in California. According to a recent report from CapRadio and the California Newsroom, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom overstated the success of forest management projects and slashed around $150 million from the state’s wildfire-prevention budget.

But Newsom — who butted heads with former president Donald Trump frequently regarding the role of climate change in causing record wildfires — has already secured $37 million in federal grant money for Sonoma County as part of a FEMA program.

It was a move announced by President Biden at a June 30 meeting with governors, key Cabinet members, and leaders from FEMA and major utilities, and senior White House staff.

Biden pointed out that there are more out-of-control fires burning now than the same time last year, with already about 9,000 firefighters deployed across the West.

“Fire season, traditionally, lasts through October. But with climate change — climate change driving the dangerous confluence of extreme heat and prolonged drought — we’re seeing wildfires in greater intensity that move with more speed … and [last] well beyond traditional months — the traditional months of the fire season,” Biden said. “And that’s a problem for all of us.”

In the Grand Canyon State, local officials are highlighting terrifying drying trends.

Lake Mead — which holds water for cities, farms and tribal lands there and in Nevada, California and Mexico — has declined to its lowest level since it was filled in the 1930s as the Colorado River continues to shrink.

The system is shared by seven states and Mexico, but not everyone in those states was utilizing the sources. The Ute Water Conservancy District in Colorado announced Friday that it would dip into the Colorado River for the first time in 65 years due to drought concerns.

With fire officials reporting reservoirs at low levels and fires larger and hotter than ever, Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management spokesperson Tiffany Davila has her work cut out for her.

In an interview with Fox News on Thursday, Davila noted that around 60% of the state was in the highest category of drought, and there was more widespread fire activity and larger incidents — though “signs of a monsoon season” and forthcoming precipitation were positive.

In this photo provided by Joseph Pacheco, a wildfire is seen burning in Globe, Ariz., on Monday, June 7, 2021. (Joseph Pacheco via AP)

“If we really start to see our monsoon activity pick up, I think we won’t see as many acres burned as we did last year,” she said.

Last year’s wildfire season was the second-worst in Arizona since 2011, with 1,087 fires and 544,113 acres burned.

Fire crews are currently fighting at least eight blazes, ranging from 25 acres to a couple thousand acres, including the Backbone, Tiger, Castle and Rafael fires and others sparked by lightning.

Another difference this year is that there are closures in place in the state, with recreational use barred on most Forest Service and all state lands.

Temperatures in Arizona have played a role in decision-making as vegetation in the state is “pretty much a tinderbox,” according to Davila.

Phoenix set a record for the hottest June in the city’s history.

“Due to the lack of precipitation that we have had, it’s basically kindling,” she said. ” So, when you take the drought-stricken fuel coupled with the extreme heat, the wind that we’ve had this year and then — in some places, you know, where a fire may start — the topography, the terrain: all of that can go into how active a fire is.”

The Coconino County Sheriff’s Office blocks off a U.S. Forest Service Road outside of Flagstaff, Ariz., on Monday, June 21, 2021. Dozens of wildfires were burning in hot, dry conditions across the U.S. West, including a blaze touched off by lightning that was moving toward northern Arizona’s largest city. (Brady Wheeler/Arizona Daily Sun via AP)

Forecasters are calling for a wetter-than-average July across the Southwest, but a drier than normal month is expected across the northern U.S. and Pacific Northwest.

Dismal snowpack totals across western mountain regions were an early indicator that the decades-long drought would strengthen and persist, The Arizona Republic reported in April.

The newspaper highlighted research from the American Geophysical Union that showed the longest dry spells between measurable precipitation increasing by more than two days per decade, with precipitation declining and temperatures increasing.

About a year earlier, bioclimatologist and hydroclimatologist Park Williams — now an associate research professor at UCLA — published a study in the journal Science suggesting the West may be entering into a megadrought worse than any in the historical record.

Speaking with Fox News on Friday, Williams said that the heat waves in 2020 and this year have been “just totally shocking,” with temperature leaps of five to 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

Williams examines how drought and forests interact in the West, focusing on tree ring records and forest surveys.

“Of all the various things that I’ve looked at, wildfire is just such a straightforward and strong drought impact. Where, if you look at the amount of forest area burned in a given year in the western U.S. and then you look at climate variables like the amount of days it rains this summer or what the vapor pressure deficits was in the atmosphere – which is basically dryness in the atmosphere – then all those variables go hand-in-hand,” he said.

“Which kind of blows me away, given that fire is inherently a chaotic event… The outcome of any given fire is determined by tons of randomness… But the amount of area burned turns out to be totally predictable based on climate data.”

Williams said scientists first noticed the relationship between fire and climate in the early 2000s, hoping that there could be “some rule” about the size of fires. Now, the average wildfire year creates 10 times more burned area than it did four years ago and every degree of warming expands the devastataion.

“That means that for the next few decades, there’s still a lot more in store, I think. It seems like it’s been really dramatic, a huge increase in fire,” he said. “But if you look at the amount of forest area that’s actually burned in the western U.S., in the last 40 years, only about 15% of western U.S. forest has burned. Meaning that 85% is still sitting there totally intact, ready to burn. And so, it’s going to be a long time before we start pushing up against the upper limit on how big fires can get.”

So far, 2021 already ranks as one of the driest years of the last 120, and with what is considered “normal” changing due to climate change, adjusting to heightened wildfire seasons will be crucial to ensuring survival.

Is there a solution?

Williams said “the writing is on the wall” in terms of the urgency in tackling climate change, but getting leaders to agree to needed action remains difficult.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

Major prescribed burns in some areas, for example, could lessen the risk of severe wildfires, but he questions the resolve to take such action.

“We have 100 years of bad decision-making to make up for, and it could take 100 years of good decision-making to really make up for it,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Source: Read Full Article