Phil Martin walked through the flames, smoke, rage, hate and blood when Moss Side was burning in 1981. It was where he was from, those were his streets.

He had a vision as he stepped lightly through the carnage, a man with respect on all sides at a time of lethal division. A fighter, a car mechanic and a man people listened to. He had big ideas.

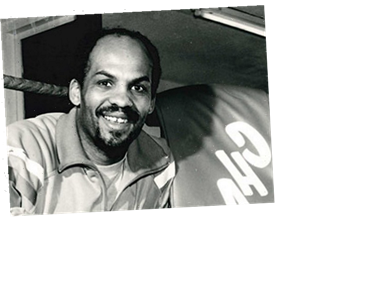

In 1976 Martin lost a British title fight over the full 15-round distance. Harold Wilson and Edward Heath were the ringside guests that night at the Grosvenor House in London’s Park Lane. Martin finished his pro career in 1978 with 14 wins and six defeats. When he quit he decided to open a boxing gym.

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

At the end of the riots the fighter found an abandoned building, still smouldering and he built his gym in the ruins. There were no quick fix solutions to the riots of 1981, there never is, and scarred cities like Manchester often had to find their own ways to improve. Martin made a gym, begged and borrowed and called it Champs Camp; a mural of Muhammad Ali eventually covered the outside wall. It was the Neil Leifer picture from the 1965 fight with Sonny Liston – the one where Ali is telling Liston to get up. That was the perfect Ali image to look down on a damaged city, a face full of anger and pride.

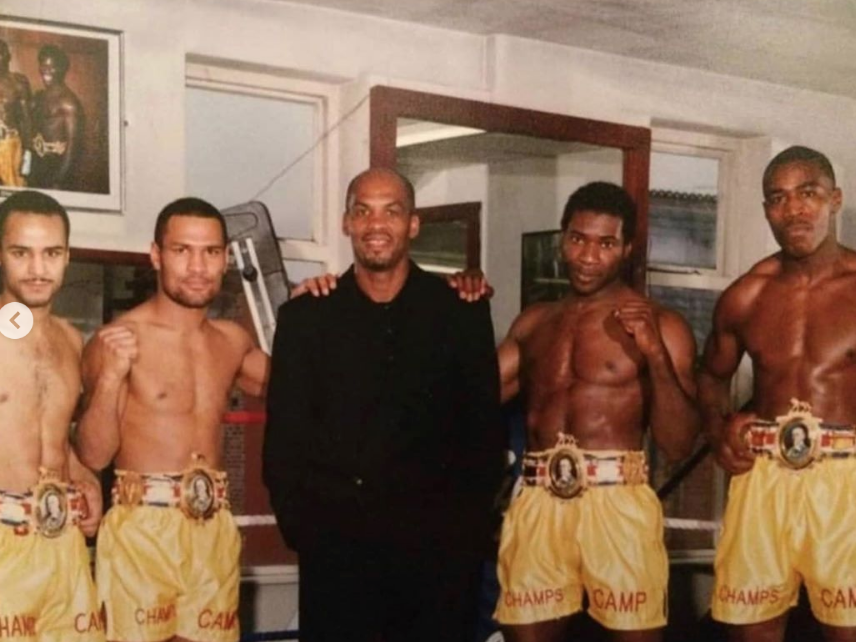

Big Phil kicked out the men and women desperate to jump on his multi-coloured rainbow, he showed them the same battered door he opened and closed on the street gunmen. Martin was never bothered about a satisfying cliché; nobody was getting a free ride on Martin’s horse, make no mistake. Still, he gave identity to a lost part of Manchester, he delivered British champions and at one point in 1993 he had four in the gym; they were men with pictures in the paper for the right reasons, smiling and holding their Lonsdale belts. That is old, old pride.

Not surprisingly, Martin was not embraced at the time and there were still many in the boxing business who wanted to ignore him, including the media. At one show he promoted on a Sunday in Oldham in 1993, when his four British champions boxed and another was fighting for the British title, I sat with just one other national newspaper reporter. The man from The Daily Sport, by the way. Can you imagine that now? An independent, black gym owner, trainer, promoter and manager with his black, mixed-race and white fighters staging a sell-out show? Can you imagine? It was nearly 30 years ago and we have not seen anything like it since. Those were, trust me, still bad days in British boxing if you were not with one of the big promoters.

Phil Martin, you see, did things his way, said some things that were harsh and he was not always easy to get on with. He died in April of 1994, one of British boxing’s forgotten men. Martin left behind his ideas, his fighters and other refugees from the streets, men who found sanctuary up his stairs, throwing punches in his mirrors and wondering what to do next. Men under Martin’s supervision – Billy Graham and Joe Gallagher – went on to have their own world champions. Martin also had his own science of decency and could reject a local MP or welcome a kid with a fresh wound. “They come in and say ‘I can’t’. I have to say ‘You can’,” Martin told me one night.

“He gave everybody a chance,” Maurice Core said. Core won the British light-heavyweight title for Martin. Core was also held in Strangeways on nine attempted murder charges – “Nine, can you believe it? Nine.” – before being cleared and heavily compensated. He became a school governor, helped keep the gym open and has helped keep the peace. “Even now in Moss Side, everybody has a Phil story.” Many have a Maurice Core story. When Martin died it was left to Core to deliver testimony at the service in a converted TV studio, a place where Martin promoted fights, in Moss Side.

In 1993 there were over 100 shooting incidents in Moss Side and I went to talk with Phil at the gym; two bullet-proof vests were hanging on hooks in the changing room. I knew the owner of one, he had recently been shot, it was not a case of mistaken identity and he could really fight. “He is the best fighter in the gym,” Martin told me that day. It was also known that the kid was a hitman – the police confirmed that.

Chris Eubank, world champion at the time, who had a cousin who fought for Martin, was in Moss Side on his own mission. A kid called Benji Stanley, just 14, had been blasted by a shotgun at Alvino’s Pattie and Dumplin’ Shop, close to the gym. Eubank arrived for his seven-day tour with the purest of intentions – I’m convinced of that – to be part of a march to keep the complex Stanley story active. Core was part of the march, the Stanley death was just the latest, but it was bloody in ‘Britain’s Bronx’, one of the nicknames. However, Martin was not having the incursion, he was never in a hurry for a photo opportunity.

“I have been here for 20 years, he’s been here 20 minutes and he’s getting all the publicity,” Martin told me just minutes after Eubank had visited the gym. “I was listening to him go on and I just told him to shut up and f*** off. I’d heard enough.” Martin had also seen enough.

There are still men from Martin’s gym with blood vendettas hovering over their heads, unable even now to travel to certain parts of Manchester or even through parts of the city to reach a destination. Men with wounds, war stories, love for Phil and Lonsdale belts in their history. There are a lot of dead in this story, Phil could not save them all. The hitman, who also fought on the Oldham bill, is still alive and kicking. I saw him at funeral last year in Salford. It looked like he still had on his bullet proof vest.

Martin might just be the perfect candidate to have his head placed high on a marble plinth somewhere in the city he helped during some truly terrible days. He would get my vote for a statue.

Source: Read Full Article