With each day comes a new crate of tea leaves, hints and clues of what’s to come, and when. We gauge ebbs and flows of “momentum” — toward the resumption of sports, away from it, who wants to play, how can they play, will they be safe, will the people care?

NBA superstars hold a conference call, and the message is this: ‘We want to play.’ The NHL commissioner expresses confidence in a 24-team playoff. The governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, declares his state “a ready, willing and able partner,” says “the state will work with [teams] to come back.”

It is impossible not to feel small jolts of hope.

Always, though, there is the thousand-pound buzzkill in the room.

Always, there is the bottom line, especially in the sport so many have entrusted as being the guidepost through all of this — baseball. It is baseball that has begun to aggressively get its house in order, issuing a thorough 67-page outline of protocols and procedures designed to ensure a safe return. It is baseball that has thrown the most spaghetti against the most walls, gaming out plans that make the most sense.

And it will be baseball that must, eventually, discuss and debate what will surely be the sourest aspect of all of this: whether players will agree to play for the prorated portion of their contracts, which is what the Players Association wants, or if they’ll agree to a strict (and, for now, temporary) revenue-sharing split.

We are, of course, in absolutely no mood for this bickering as a nation, and will have no patience for the perennial quarrels between millionaire players and billionaire owners. There are, at last count, 36 million out-of-work Americans. The COVID-19 death toll will soon surpass 100,000. In other times, Blake Snell might simply be dismissed as just another chatty baseball player with little self-awareness.

In these times, he might well become a pariah of piggishness, the very symbol of self-indulgence, if this labor civil war actually draws blood.

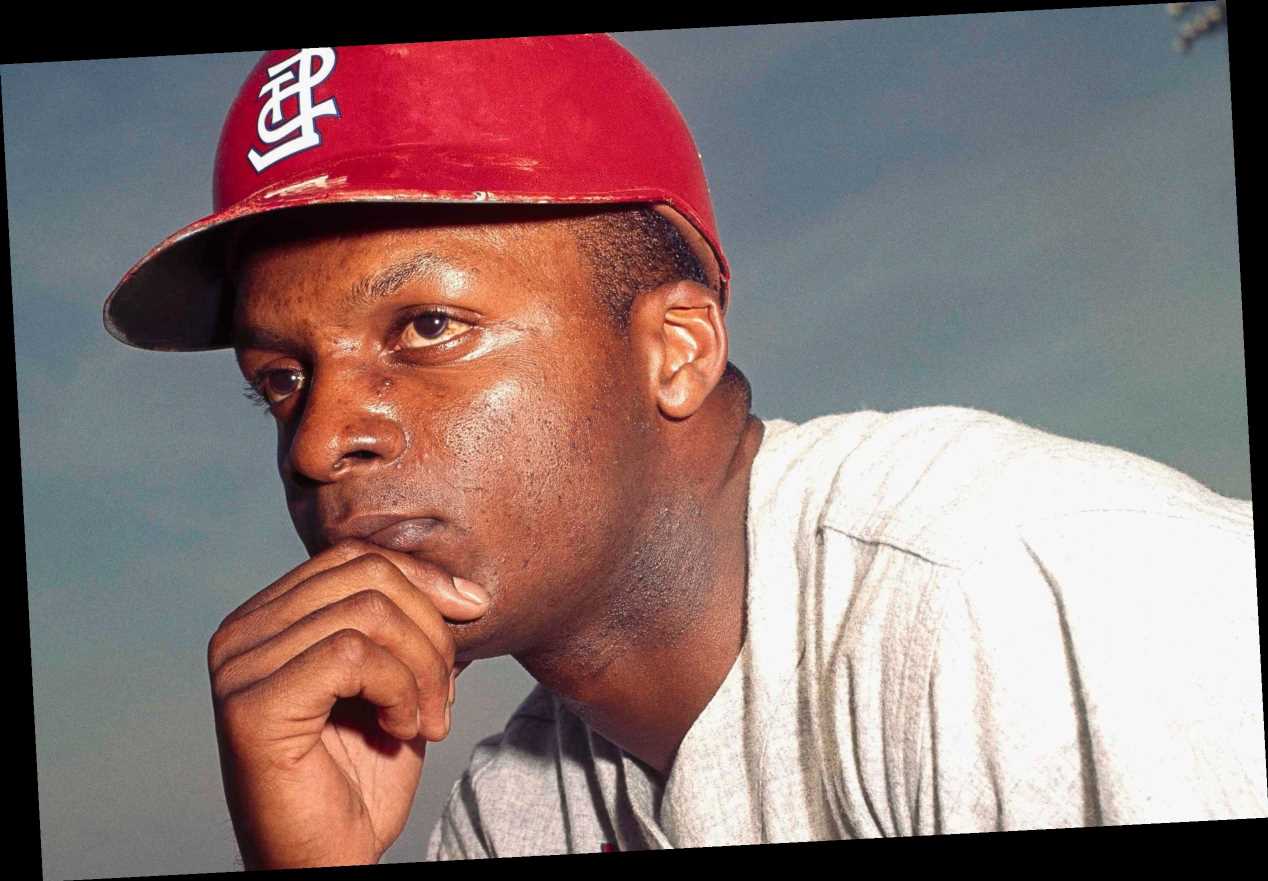

The players, after all, have never enjoyed support in the court of public opinion in any of this, no matter how noble their cause might be. It is a useful coincidence that 50 years ago this week, inside room 1505 of the federal courthouse at Foley Square, Curt Flood squared off with MLB in the first genuine showdown over the fundamental rights of players.

The reserve clause had existed for a century, a standard part of a baseball contract which, in essence, bound a player to a team for life, unless the team chose to trade or release him. Players railed against this for years but the standard reply, every bit as loud in 1920 as 2020, was this: Shut up and play.

Flood had been traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies after the 1969 season. He refused to report to Philadelphia. He chose to challenge the reserve clause in court, backed by the union, and much of the theater of Flood v. Kuhn was equal parts comedic and infuriating. At one point, as Flood nervously gave testimony, the judge, Irving Ben Cooper, interrupted.

“I presume you are not finding this as easy as getting up to bat,” he said, and it is impossible to believe he ever said something like that to a jumpy plaintiff in, say, any wrongful-death suit he oversaw. Flood was actually asked to recite the back of his baseball card at one point. But his most compelling testimony has lived on, eternally, as the lasting battle cry of the MLBPA:

“I didn’t think that after 12 years I should be treated like a piece of property,” he said.

Flood, famously, lost the case and, in essence, sacrificed his career for the cause, but the union was forever emboldened. It was a pyrrhic victory for baseball, which has endured 50 years of bludgeonings by the union, making up for a prior century of paternalistic power. The two sides were already headed for confrontation in a year. The pandemic has sped up that schedule.

Whether the rest of us are ready for it or not.

Source: Read Full Article