‘Missing’ microplastics have been found on the seafloor in the largest quantities ever recorded with nearly two million pieces per square metre.

Oceanographers have finally traced the evasive microplastics to massive plastic hotspots which have accumulated on the deepest seafloors.

Up to 1.9 million pieces of microplastics were discovered within just one square metre of the ocean bed, according to European researchers.

Nature programmes such as The Blue Planet sparked public outcry about the amount of drinking straws and carrier bags polluting our oceans.

But such waste accounts for just one per cent of the 10 million tons of plastic entering the world’s oceans, the researchers said.

Until this study it was unclear where the missing 99 per cent actually ended up.

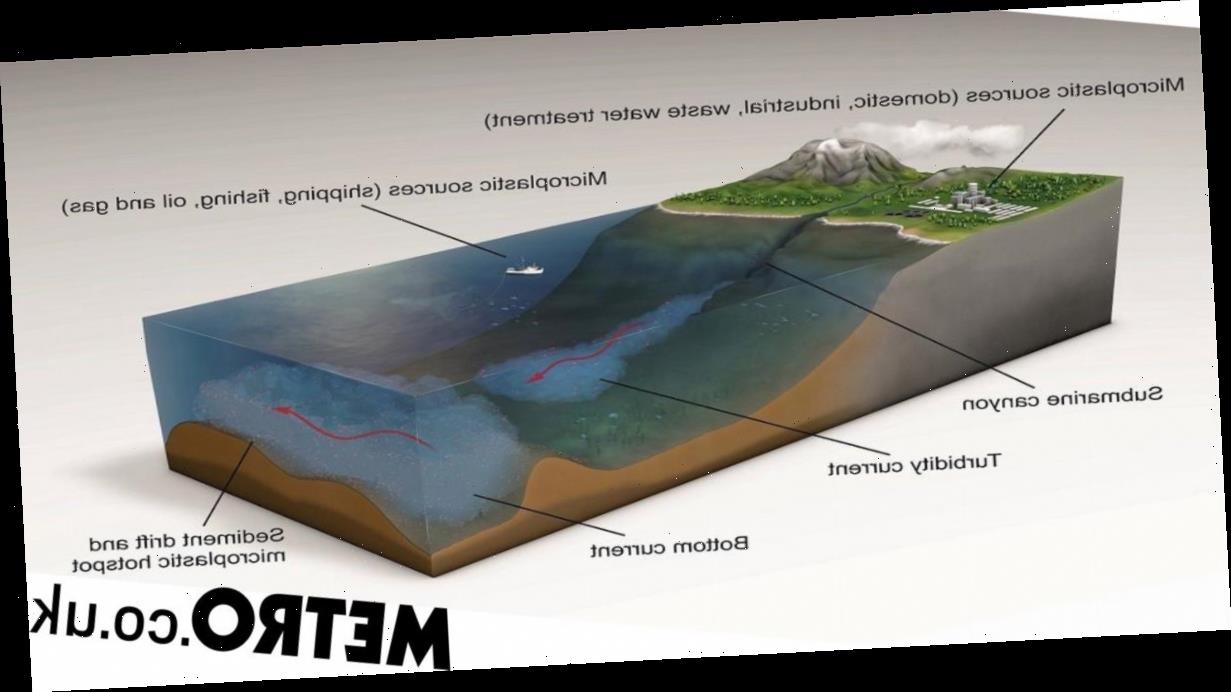

The tiny fragments had been hard to locate because currents of deep-sea ‘conveyor belts’ had dragged them deep into the ocean through submarine canyons, the team explained.

Study leader Dr Ian Kane, at Manchester University, said: ‘Almost everybody has heard of the infamous ocean ‘garbage patches’ of floating plastic, but we were shocked at the high concentrations of microplastics we found in the deep-seafloor.

‘We discovered that microplastics are not uniformly distributed across the study area; instead they are distributed by powerful seafloor currents which concentrate them in certain areas.’

In the study, published in the journal Science, revealed that deep-sea currents are concentrating microplastics in huge sediment accumulations, which they termed ‘microplastic hotspots’.

These hotspots appear to be the deep-sea equivalents of the so-called ‘garbage patches’ formed by currents on the ocean surface, according to the team which included experts from Durham University and the UK’s National Oceanography Centre.

The microplastics amassing on the seabed are mainly shed from textiles and clothing. They evade filtering at sewage treatment plants, and easily enter rivers and oceans.

In the ocean they either settle slowly, or are flushed away by powerful underwater avalanches, known as ‘episodic turbidity currents’ – that travel down submarine canyons to the deep seafloor, the scientists explained.

Once in the deep sea the microplastics are readily picked up and carried by continuously flowing seafloor currents that merge the waste within large drifts of sediment.

The seafloor, far from an empty expanse, often houses important ecosystems thanks to the oxygenated water and nutrients that the deep ocean currents deliver.

But in addition to rich nutrients, the currents are now transporting microplastics too which interferes with habitats that sustain marine life.

This study provides the first direct link between the behaviour of these currents and the concentrations of seafloor microplastics.

The team collected sediment samples from the floor of the Tyrrhenian Sea, which lies within the Mediterranean Sea.

They combined the samples with calibrated models of deep ocean currents and a detailed mapping of the seafloor.

Back in the laboratory, the oceanographers separated the microplastics from the sediment, counted them under the microscope, before analysing further using infra-red spectroscopy to determine the plastic types.

Using this information the team managed to show how ocean currents are controlling the spread of microplastics on the seafloor.

The team said it is ‘unfortunate’ that plastic has become a new type of sediment particle mixed together with sand, mud and nutrients.

Study co-leader Dr Mike Clare, of the National Oceanography Centre, UK, said: ‘Our study has shown how detailed studies of seafloor currents can help us to connect microplastic transport pathways in the deep-sea and find the ‘missing’ microplastics.’

He added that policymakers should act now to limit the future flow of plastics into the oceans to reduce damage to marine life.

The team said the findings could help predict the locations of other deep-sea microplastic hotspots and also guide research into how marine life is dealing with the invading microplastics.

Source: Read Full Article