If there’s any truth to the old William Blake line about the road of excess leading to the palace of wisdom, then Peter Gatien may be the wisest cat in New York.

At least, he was the wisest one in the lobby bar of the Bowery Hotel one Saturday afternoon in mid-March. But then, we did have the place to ourselves. The coronavirus had claimed its first New Yorker that morning and the usually jumping East Village boîte was barren. Gatien, 68, once the undisputed king of nightlife in the city known for excess, was dressed casually in a car coat, hoodie, and blue jeans, with New Balances on his feet and chunky white headphones around his neck. He plopped down on the wicker furniture and ordered an iced tea. Between sips, he spoke with some disappointment about his return to New York, which had blackened both his eyes and then bounced him nearly two decades ago like a drunk from a bar. “It’s not as good as it used to be, I can tell you that right now,” he says. “There’s not even a sketchy neighborhood in Manhattan anymore.”

But it’s boring to complain about how New York is now boring. No, this prodigal son has not returned from Canadian exile to whine about the Wall Street invasion of Williamsburg or the death of Dean & Deluca. Rather, he’s got a tale to tell, one filled with fabulousness and tabloid phantasmagoria — and it ain’t boring.

Related

After Hanukkah Stabbing, Some Ultra-Orthodox Jews Are Arming Themselves

Murder of Tessa Majors Exposes Some NYPD Cops' Conservative Stance

Related

10 Best Country Music Videos of 2019

89 New Christmas Albums of 2019, Reviewed

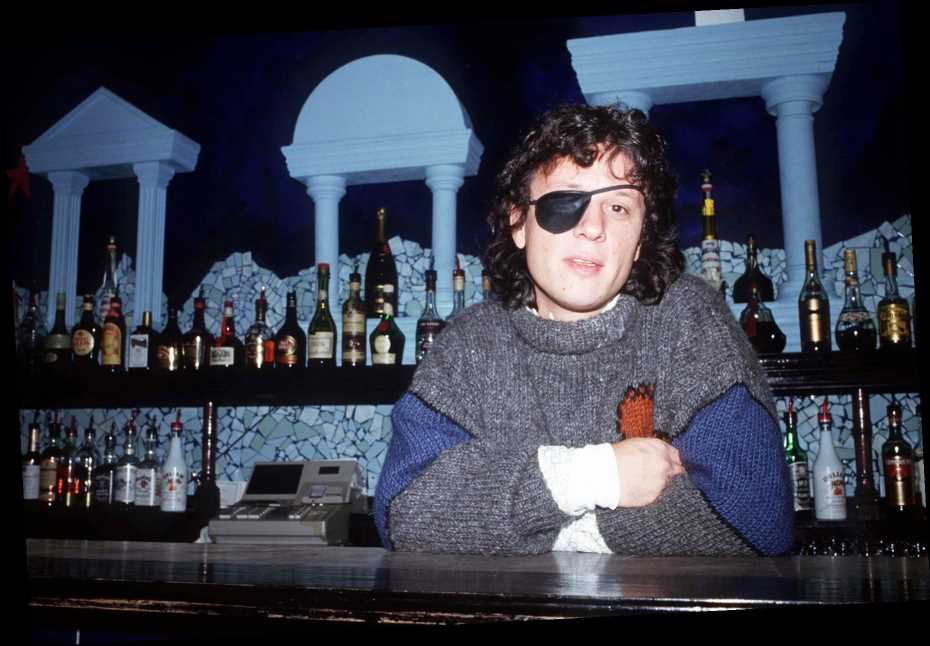

Once upon a time, before Twitter, Tinder, and Tik-Tok — before blogs and bottle service, even — culture was born in nightclubs. In them, fashion designers found inspiration for their next runway show and record execs found their next big hit. A thriving downtown press corps had to go out seven nights a week to tell readers the who, what, when, where, and why of cool. Coolness could always be found at one of Peter Gatien’s mega-clubs. At his height in the 1990s, Gatien commanded a sprawling empire. In Times Square was Club USA, an adult playground complete with a slide and interior design by Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler. The raucous Palladium (now an NYU dorm) was down on 14th street, while the Tunnel was situated on the far west side and was “hip-hop’s most sacred ground,” as VIBE magazine put it. Most notoriously there was the Limelight, a deconsecrated, gothic-style church on Sixth Avenue at 20th Street in Chelsea (now a SoulCycle knock-off). As Jay-Z once rapped about the eye-patch wearing emperor of clubland: “Me and my operation runnin’ New York night scene with one eye closed like Peter Gatien.”

Gatien, who lost an eye in a childhood accident, prefers to think he was runnin’ things not with one eye closed but with one fully open. Either way, he saw enough to fill a book, and that’s precisely what he’s done. The Club King, his slick new memoir out this month, chronicles Gatien’s rise from a working-class kid in a sulfurous paper mill town in Ontario. His story may get the Hollywood treatment too, with a script already in the works by Nicholas Pileggi — best known for writing Goodfellas — and Amazon Studios set to produce. Gatien is also involved in a Sacha Jenkins-directed documentary that will focus on the Tunnel’s place in the pantheon of hip-hop.

“You’ve got to understand,” says Gatien, “Tunnel in those days, the whole industry was there.” Asked to riff about the years he spent ladling the primordial soup of gangster rap, Gatien remembers wild nights with ease:

“We used to have a marquee at Tunnel and Tupac walks out, sticks his gun up and ‘bang, bang, bang.’ Who the freak knows? He wasn’t like ‘I’m gonna shoot everyone!’ [He shot] just the marquee, and then he kept walking. Tupac was too cool for words.”

What about 50 Cent? “He was so small back then, he must’ve been 15 or 16. I sort of remember him bickering with security, but he got in.”

Lil Kim? “Her entourage was always a nightmare… She was trouble.”

He writes about the night Biggie died, when Funkmaster Flex played “Hypnotize” before a crowd of 2,000, crying silently. Not to mention all the gadabouts who played and partied at his other joints, from Prince to Axl Rose.

“I remember agonizing about paying Moby three hundred dollars, thinking ‘Is this guy really worth it?” Gatien says with a laugh. “I’ll tell you one thing — at those keyboards, he really did lay it all out there.”

None of it would have probably happened if he hadn’t lost his eye when he was six-years-old. A myth was always perpetuated about the Canadian expat losing it during a hockey game, but actually baseball was to blame. His schoolyard pals had been using a broken, jagged broomstick as a makeshift bat when it slipped from one kid’s and connected, like a javelin, with young Gatien’s left eye.

“I never liked talking about it,” he says now. But the loss did provide him with a few things. He notes that, once he began to wear his signature black eye patch, he “instantly became a member of a select fraternity” that included James Joyce, Bazooka Joe, Snake Plissken, and David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust. (During our interview Gatien opts for a pair of electric blue Christian Dior shades instead, saying “I don’t wear a patch much anymore, if at all.”)

The accident also resulted in a settlement from the school, which Gatien used in part to open a denim shop in 1971, which he called the Pant Loft. That business later allowed him to purchase a bar — his first nightclub — that he named the Aardvark, after the character in the Saturday morning cartoon The Ant and the Aardvark. A third eye for spotting talent was honed early, too, as he recalls one of the first gigs he booked, an up and coming local group called Rush.

He married his high school sweetheart and had two daughters, but America — and disco — beckoned. Soon he split his time between Ontario and South Florida, where he acquired a run-down called Rum Bottoms and rechristened it the Limelight. His eye for talent paid off here, too. Grace Jones and Gloria Gaynor rocked the club and he took a chance on a weird act called the Village People, booking them four months in advance. Then, on the eve of their performance, “Macho Man” hit the airwaves. Suddenly, Gatien writes, “I had the hottest act in the country.”

In 1978, he opened another Limelight, in Atlanta, Georgia, that would come to be known as “the Studio 54 of the South.” In a Tiger King-style flourish, Gatien built an enclosure beneath the glass dance floor and stocked it with a live panther. Today he cringes at the idea, but the big cat roaming under dancers’ feet presaged his preternatural ability to drum up press and controversy — an ability that would make him, but later destroy him.

Peter Gatien (right) with singer George Michael in New York City, circa 1987. Photo credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

At last, in 1983, Gatien made it to New York. The city was such a smoldering pile of rubble then that he was able to purchase the abandoned “Church of the Holy Communion” in Chelsea for just $1.6 million. Gatien, a self-described lapsed Catholic, writes that when the church learned of his plans, the Episcopal bishop of New York gifted him with a “three-word, worth its weight-in gold review”: “We are horrified.”

The place drew a hell of a mass from the jump. Every boldface name of the roaring Eighties partied there, from Madonna to Donald Trump. (“He was always uncool,” Gatien says of the current commander in chief, with a dyspeptic smile.) In Florida and Atlanta he’d learned how the lifeblood of a swinging disco depended on the gay quotient. “My whole thing was always that to try to get an eclectic crowd in the place, you need a gay presence,” he says. “They’re really good for the energy, and I often saw sort of rough looking guys from Brooklyn or the ‘burbs and all the sudden they’d be mixing and they’d realize ‘These people aren’t so bad.’” Then the AIDS crisis hit, petrifying the city. No one wanted to party. The gilded Bonfire of the Vanities New York was over.

In the early Nineties, hope bloomed anew as people began to understand more about the virus, like the fact that it couldn’t be spread from sharing a drink. Alas, all the stars had since moved on from the Limelight and the club was sputtering. That left room for something new. What came next to the club was not glitzy, but plenty kinetic. “The second ever electronic music performance I had was at Limelight,” Moby tells Rolling Stone. “It was 1990, I had just started making records but I was still this innocent, naive, almost Dickensian kid in the big city.” He says that before the Nineties he wouldn’t have even tried to enter the club but that “by 88 or 89 it had really become a sad nightclub that no one even though about [it], which is why Michael Alig and Lord Michael were able to start their nights.”

These two party-promoting Michaels represented a shift in nightlife. Their parties gave rise to the so-called Club Kids, a pioneering group of ecstasy-addled downtown personalities known for dressing in elaborate drag and pulling outrageous stunts. It all dovetailed with the rave music coming over from London at the time.

Moby describes the new scene: “Everybody was accepted and at Limelight you would walk in and there were drag queens and muscle bound guys from Brooklyn and cute little ravers from F.I.T. and the suburbs, and it was Asian and it was African American, it was Caucasian, it was straight, it was gay and in hindsight it was really precious, but at the time it just seemed normal. We just sort of accepted that the outside world had been ravaged by AIDS and crack and you created these little utopian microcosms in nightclubs.”

“It used to be a lot more egalitarian back then,” says Gatien. “I valued customers more for what they could contribute to a party than whether they bought six bottles or whatever.” Reconnoitering today’s dreadful scene, he says: “God, you go to a place like 1Oak” — the Meatpacking District club favored by Instathots and their investment-banker boyfriends — “and you get a table, it’s costing you a thousand dollars. There’s no legacy to those places and there never will be.”

“Peter was obscure in a Citizen Kane, Jay Gatsby-esque sort of way,” says Moby of Gatien in those days. “You would just see him hovering at the edges of nightlife, but you never saw him speak, he never engaged with people, he always wore that eye patch, so he just looked remote and terrifying… he was like a Bond villain.”

In a hectic nine-month span in 1992, Gatien grew his empire — acquiring leases on the faded Palladium and Tunnel, and erecting Club USA — packed ‘em in and raked the bucks by the millions. And along came Rudy.

Rudolph Giuliani squeaked into City Hall as Mayor in 1993 by just 50,000 votes, buoyed thanks to a Staten Island secession referendum on the ballot that year. (They love Giuliani on Staten Island). As part of his new “Quality of Life” initiative, Giuliani went after hot dog vendors, buskers, jaywalkers, street artists and squeegee men. Even J.J. Hunsecker did not relish shooting mosquitoes with an elephant gun the way Giuliani did.

“And then he ran out of squeegee people,” says Gatien, “and I was the face of nightlife back then.” In that brooding, eye-patch clad visage Giuliani found the perfect, tabloid-ready target for his moral crusades.

“There had been a sense that the city was ungovernable,” says Fred Siegel, a Giuliani biographer who helped author his “Quality of Life” speech in 1994. “The Limelight and the Palladium were seen as part of that un-governability, that this was a Wild West zone which you could do pretty much whatever you wanted… the people who lived in proximity to those clubs wanted them out,” Siegel says.

The newfangled Mayor — who already had a reputation for overreach from his time as United States attorney for the Southern District of New York — didn’t have to look far for ammo to use against Gatien.

The world in which Gatien operated was crawling with characters of ill repute. One such character was promoter Michael Alig. In 1996 Alig, doped out on a mix of heroin, cocaine, rophynol, and ketamine, murdered fellow club kid Angel Melendez. The brutal nature of the killing — Drano was used in some capacity and body parts washed up on Staten Island months later — made it one of the decade’s most notorious crimes. It didn’t matter that, by the time it happened, Alig had long since been fired by Gatien. The media glare blew up the spot. “The whole [club kid] movement got tainted because of what he did,” Gatien says. Alig would serve 17 years in lock-up and, once he got out in 2017, began throwing parties in New York. Gatien says he has no desire to be in touch with his former employee. Indeed, the killer club kid gets about as much ink in Gatien’s book as the disco panther from Georgia. (Though Gatien does admit it was “flattering” to be played by Dylan McDermott in Party Monster, the 2003 film depicting Alig’s rise and fall).

Things were compounded by the fact that Gatien himself had developed an epic drug habit, sometimes renting out suites at the Four Seasons for days-long benders. He eventually kicked the stuff, but credit card bills bearing proof of his binges were later aired out in court and didn’t exactly help his case.

Law enforcement described the clubs as “drug supermarkets” and the titillating term was reprinted ad nauseum in the newspapers. When a New Jersey teenager was found dead at home after a night of partying at the Limelight, his politically connected parents caught the attention of Giuliani — never mind the fact that the medical examiner later concluded the cause of death was suicide by hanging. The Savonarola in City Hall sicced the dogs on Gatien. “The New York Post back then was literally a newsletter for him,” says Gatien. “The Post attacked me like I was friggin’ John Gotti or worse. It was just merciless, daily.” In particular it was the late Jack Newfield, a Post columnist, who spun any crime that occurred at one of the clubs into an assault on Gatien’s character.

Once Operation Get Gatien kicked into third gear, he writes, DEA agents outfitted in get-ups from Patricia Field’s boutique began prowling the Limelight in search of small-time drug deals. The U.S. Attorney’s office flipped a rogue’s gallery of Limelight regulars and small-time dealers, including a drugged out Alig, dangling freedom in exchange for damning testimony against Gatien.

Main dance floor with mezzanine slide at Club USA, 1992. Photo credit: © Tina Paul 1992

By the time the case went to trial in 1998, the prosecution felt it had enough to convince a jury that Gatien was a menacing crime boss who orchestrated an elaborate drug ring. (A more accurate picture would have a depicted an out-of-control nightlife impresario high on his own supply and in over his head). The trial was a fabulist farrago from the start. Informants who had flipped on Gatien flipped back to his side, claiming the government put words in their mouth and then some. The prosecutors’ willingness to fish out of the gutter any old scoundrel willing to sing in tune ultimately backfired. As one juror, a 62-year-old tractor-trailer driver, later said: “These witnesses, they lied so consistently, how could I believe them?” Gatien had enlisted as his defender Ben Brafman, the celebrity attorney then-preferred by Gambino mafiosos. Brafman was so sure of the cracks in case that he didn’t bother calling any witnesses for the defense. After an five-week trial, the jury cleared the Club King in just a few short hours.

“I think the Peter Gatien acquittal still stands out in my mind as one of the most thrilling,” says Brafman, who would later win legal battles for P. Diddy and Dominique Strauss-Kahn. “Deep in my heart I thought that the way the government conducted itself during that trial was offensive.” Still, he says, “it took away a chunk of Peter’s life.”

Afterwards, Gatien did all he could to beef up security, even hiring a former special narcotics prosecutor to monitor his clubs. But it wasn’t enough. He was harassed with regular raids and shutdowns until the mounting legal fees left him banjaxed. And then the tax man got him. In 1999, he pleaded guilty to tax-evasion and paid over a million dollars in back taxes — a sum he likens to a rounding error given the amount of dough that was rolling in back then. He pleaded out to two months in Rikers. The biggest gut punch of them all came in 2003, when Gatien was deported. In the more than 30 years he lived in America, he had never bothered to obtain citizenship. With his wife and youngest child — he had since remarried, twice — still in New York City, he was suddenly alone and back in Canada, where it all began. There was nothing left, save for the $500 in his pocket given to him by his attorney. (The family joined him in Toronto soon after).

“This is the perfect example of what happens when the government loses,” says Brafman. “They don’t like to lose, and because they’re the government, they find a way to win.”

Shaking his head, Gatien says “If I had to do it over again, when I got acquitted, I should have picked up my tent and moved out of the city.”

Giuliani did not return multiple requests for comment for this story. (Though he did return a call via an apparent pocket dial and could be heard for seven minutes discussing with a female aide a coronavirus related opportunity.)

After many years in the wilderness of Toronto – and a short-lived and somewhat successful stint overseeing a club there – Gatien was allowed to return to New York. For the past three years he has split his time between Toronto and New York, where he lives in Hells Kitchen. Downtime is spent kicking it with his eldest daughter, Jen Gatien, a filmmaker who lives downtown, or walking around Central Park. He thinks Brooklyn is OK, but isn’t interested in getting back in the game. “The club business? It’s a young man’s game,” he says. I tell him he sounds shockingly at peace with the way things have ended up. Consider his compatriots: Studio 54’s Ian Schrager was pardoned for his tax evasion by Obama and is now a hotel magnate. “I don’t want to come across as woe is me,” says Gatien.

“I think Peter went through a time when he was justifiably bitter,” says Brafman. The two have remained close. “They took everything from him and also removed him from the country. But I also think Peter has mellowed out over the years.” And yet, “the Gatien story is a real black eye for New York. I think Peter brought a lot of culture and talent to this city.”

Even Siegel, the Mayor’s “Quality of Life” speechwriter, describes current New York as “pretty bland.” So maybe Gatien has a right to feel wronged by Giuliani, after all? “No,” Seigel says. “The nightclub was a sewer.” How the hell would he know what the Limelight was like? “I was only in there once… I wanted to see what all the hubbub was about.” So, how was it? “The only word is: Decadent.”

But maybe it was that decadence that gave the city its aura. “The culture that made New York work,” Gatien says, “that’s what the clubs were. That’s what’s missing now — that raw energy. It’s to be celebrated. It was the last of an era.”

[Find the Book Here]

Source: Read Full Article