A distant star that was once about the size of our sun has been obliterated by a monstrous black hole — and astronomers have the whole thing on tape.

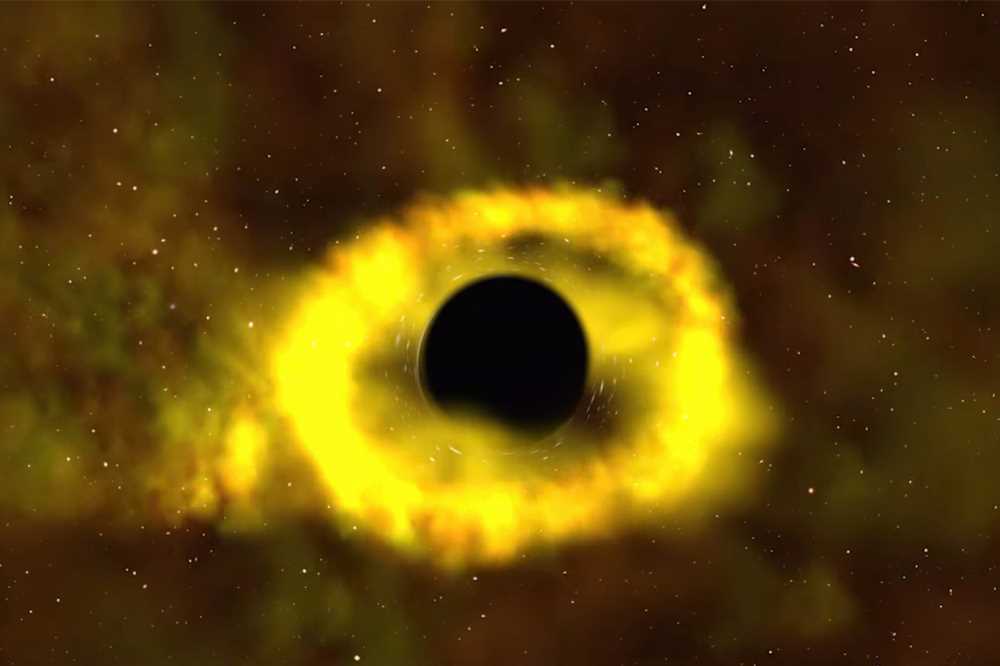

NASA’S Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has stumbled upon a cosmic cataclysm called a tidal disruption event, or TDE, which occurs when a black hole pulls a wandering star into its gravitational grip, shredding its gases and flinging star matter out into space. The result is a black hole’s signature glowing ring, called an accretion disk, which eventually falls into the depths as well.

“TESS data let us see exactly when this destructive event, named ASASSN-19bt, started to get brighter, which we’ve never been able to do before,” Thomas Holoien, a Carnegie Fellow at the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. Scientists say this new data, published in the Astrophysical Journal, reveals that TDEs are a lot more varied than they previously believed.

“It was once thought that all TDEs would look the same,” said Ohio State University researcher and study co-author Patrick Vallely in a press release. “But it turns out that astronomers just needed the ability to make more detailed observations of them.”

The discovery was made possible by a network of telescopes in South Africa and Chile, as well as the TESS, which was set up in 2018 to investigate alien planets and launched into orbit last April. Scientists have never before observed the rare phenomenon — this one some 375 million light-years away — in such stunning detail, and likely won’t again for some time. In the Milky Way, a TDE may only happen once every 10,000 to 100,000 years, according to researchers. Also, it’s not exactly common for stars, spaced millions or billions of miles from other celestial bodies, to happen upon a black hole. If they do cross paths, the star and black hole must be within a cozy distance of about 93 million miles — which is about as close as we are to the sun.

“Imagine that you are standing on top of a skyscraper downtown, and you drop a marble off the top, and you are trying to get it to go down a hole in a manhole cover,” said Chris Kochanek, professor of astronomy at Ohio State. “It’s harder than that.”

Scientists have observed just 40 such events, but none as detailed as ASASSN-19bt.

“We have so much more to learn about how they work, which is why capturing one at such an early time and having the exquisite TESS observations was crucial,” said Vallely.

Source: Read Full Article