In the 21st century, a drag queen is not just a man who wears women’s clothes; a drag queen is an entirely separate entity. When so impeccably dressed and flawlessly painted, the person underneath the queen disappears almost completely. Oftentimes, I’ve heard drag performers describe their personas as though they were another person. They’ve plunged their hands deep down into their own psyches and pulled out the weirdest, fiercest, and most theatrical parts of themselves, then mashed them together to form something new. A character. An alter ego. A super-“she”-ro, if you will.

In this moment, drag culture is bigger and more popular than it’s ever been. RuPaul’s Drag Race has just had its most successful season yet. With its move from Logo to VH1, it racked up almost 1 million viewers for the premiere and held strong with over 800,000 season finale viewers. The show’s third All Stars season is about to launch, marking a new competition between some of the top drag queens in mainstream media. And even outside of RuPaul’s Drag Race, queens have been able to build incredible followings via social media, live performances, YouTube, and podcasts.

Drag hasn’t always been received this way. In fact, this sort of public awe — sometimes, it borders on worship — of drag queens has really only cropped up in the past decade or two. Before that, drag was submerged deep in underground clubs and back-alley bars. And before that, it was an exaggerated and integral part of the theater culture. The fact is, drag has been a part of our culture for centuries. And every era and every new iteration of the art form has been crucial to the shape and success of drag today.

Where did it all begin? Few fans of the art form realize that the earliest forms of cross-dressing — simply the act of wearing clothes that are designated as belonging to the opposite sex — are actually rooted in religious rites. In his book Drag Diaries, Jonathan David focuses on two long-ago origin points: ancient ceremonies (Native American, indigenous South American, and Ancient Egyptian) and Japanese theater. David writes that “cross-dressing was widely documented among the Aztecs, Incas, and Egyptians, among other great civilizations of the past, and exists today in tribal ceremonies around the world.” Imagine religious rites of initiation, invocations of the gods, calling down the rains, and warding off evil spirits as occasions that would call for drag in these cultures.

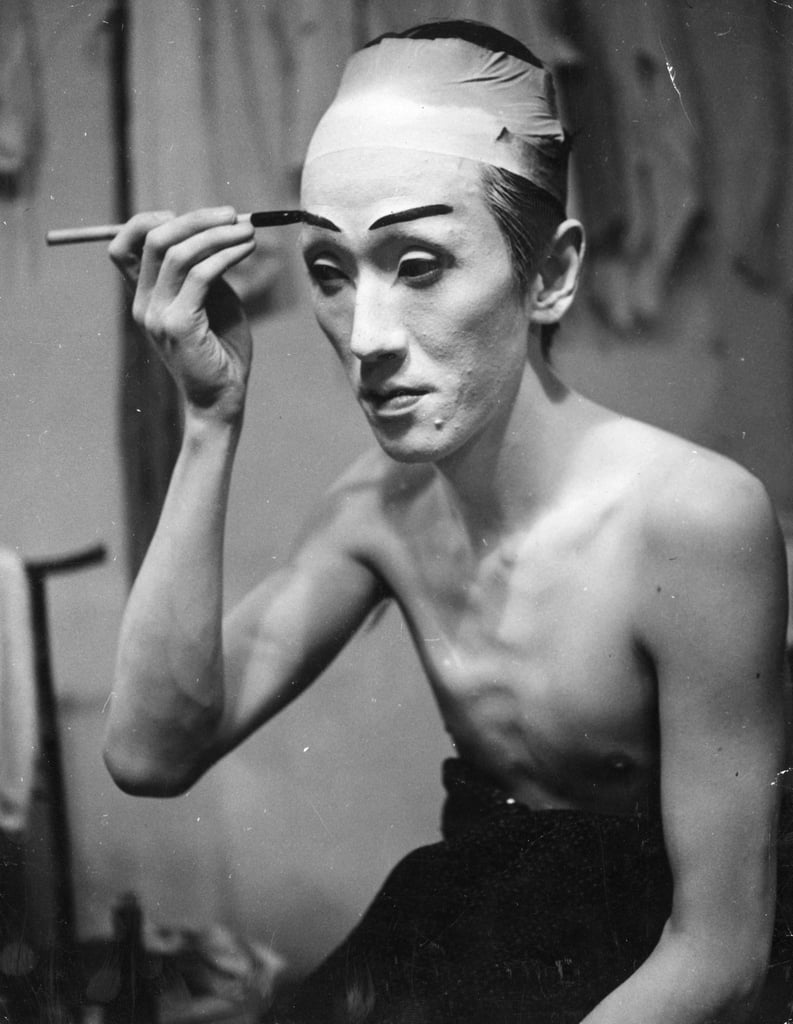

“In Japanese theater,” David writes, “drag divides the Kabuki and Noh dramas. Noh derives from Dengaku, a folk dance associated with rice planting and fertility, and in its ancient, self-enclosed spiritual world, ‘female’ actors wearing masks follow stylized routines in a complex and rarefied pattern of symbolic gestures.” Kabuki, of course, is a form of Japanese theater that many more people are familiar with. David notes that it rose to popularity in the 17th century, and “is more popular and less ritualistic than Noh.” In Kabuki theater, the female impersonators are “carefully made-up, speak in falsetto voices, and move to suggest the essence of femininity.”

Another book that shed quite a bit of light on what we might call the “sacred” drag queen is titled Drag: A History of Female Impersonation in the Performing Arts. Roger Baker also pulls a thread back to ancient civilizations, noting that drag “presided over the creation of drama in ancient Greece where masked actors played Hecuba and Clytemnestra.” Meanwhile, in England, Baker writes that “formal drama came, literally, from the church. In an effort to help the illiterate and, well, less intelligent members of the congregation better understand church worship, parts of the mass were dramatized in very simple ways.”

Eventually, these religious performances began to have a life of their own. In fact, these eclectic sets of dramas were eventually removed from the church entirely. Rather than perform the stories in hallowed chapel halls, local Guilds would instead take the reins. In fact, very specific groups would tackle the narratives most applicable to their trade. “Thus the Vintners would perform the Marriage of Cana,” Baker writes, “the Shipwrights would present Noah and his Ark, while the Goldsmiths could use the Adoration of the Magi as a suitable excuse to display their precious products.”

As for the cross-dressing component of these sacred performances, women were omitted from the craft entirely. “Women played no active part in the services and the offices of the church, so the original acting was done exclusively by men, choirboys assisting the clerks and playing women’s roles when required,” Baker notes in Drag. From there, it’s not hard to connect the dots. Recreations of these religious stories eventually were further dramatized, sometimes including subplots that didn’t exist in the original text. Before long, performances grew more secular until the dawn of a new era: original dramatic plays.

When Western theater transitioned from its religious roots to something much less sacred, the rules excluding women were kept intact. It’s worth noting, here, that the concept of drag was entirely divorced from homosexuality at this time. It wasn’t until much later that the two became inextricably linked.

In researching this piece, I reached out to Joe E. Jeffreys, a drag historian who teaches theater studies at NYU Tisch Drama. Jeffreys has chronicled quite a bit of drag culture in his own time, and archives his work on personal YouTube and Vimeo accounts. When it comes to the presence of women in the theatrical space, Jeffreys told me “it was unseemly or improper for a female to present herself on such full public display.”

In Drag, Baker writes about the earliest original “plays.” In this new iteration of theater, the performances “took to the streets with the improvisation of the strolling players livening up formal scripts. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, troupes began to use courtyards of public inns as a performance space.” Baker also notes the continued efforts to keep theater as an activity meant just for men. “To find a woman acting in a public playhouse would have offended not only on religious grounds, but also be seen as a shocking example of inappropriate behavior.”

As performance transitioned into a world of more traditional theater spaces and Shakespearean soliloquies, these ideals continued to be upheld. Baker writes of young boys who joined acting troupes and companies. “If he had a suitable face and a slim body, then his first assignments would be in female roles,” he says. “Rarely does Shakespeare, or the other dramatists of the period, introduce more than three women in any one play, which suggests that there were few boys of adequate proficiency at any given time. Smaller female roles would be doubled by by youths playing messengers, spear carriers, and all-purpose nobles.”

“A woman acting in a public playhouse would have offended not only on religious grounds, but also be seen as a shocking example of inappropriate behavior.”

As a matter of fact, the first appearances of Shakespeare’s most iconic female characters were all believed to first be portrayed by men. “The first Ophelia is thought to have been Nathaniel Field, who ultimately became as famous as actor Richard Burbage the great Elizabethan heavy,” Baker writes. “The first Lady Macbeth might have been Alexander Cooke . . . A young man called Robert (or Bobbie) Gough (or Goffe) is frequently named as the first Juliet, and also as the first Cleopatra.”

While this theatrical history provides an illustrious chronicle of men dressing as women, Jeffreys, our drag historian, made sure to draw a distinction between drag culture’s theatrical roots and the drag queen as an entity in itself. “Were the Elizabethan boy actors drag queens?” he asked. “I think the term goes beyond them.” In fact, the first true so-named drag queens didn’t emerge until the 19th and 20th centuries.

In Drag, Baker says cross-dressing remained a pervasive part of theater culture until the late 19th century, when it began to take a new form. Female impersonators developed their own vaudeville acts, wherein they created caricatures of women. Jeffreys corroborated this fact, writing that drag “was a popular act in the numerous vaudeville theatres across America from the turn of the 19th Century until the late 1930s.” This moment in time birthed such mocking personas as the “wench” and the “primadonna.” But in order to find the first iterations of the “drag queen” as we know her today, we have to pinpoint the moment drag culture became inextricably linked with the gay community.

Jeffreys told me that this link didn’t really happen until the 1930s. “Before then, the scientific field of sexology was forming and began to talk about the ‘third sex,'” he said. “The third sex was discussed as a feminine man or a masculine woman who desires members of the same sex. By the 1930s this scientific conversation had worked its way into the popular culture and linked drag with homosexuality.” This connection marked the switch: drag culture no longer belonged to straight, white men. In this moment, we witness the emergence of the first true drag queens. “Drag queens are not only males who dress and perform as female but also have some connection to a gay scene,” Jeffreys said. “Until gay bars emerged, either clandestinely or legally, the drag queen was bounded by private parties, and even then police raids were possible.” I was lucky enough to get a quick lesson in the first true gay drag queens from Jeffreys as well:

“The first true drag queens rest in little-remembered bars. Jose Sarria at San Francisco’s Black Cat in the 1950s is perhaps an early example if we go down this path. There were, of course, men who entertained as women: performing at this time in places like the 82 Club in New York City or touring the country with the Jewel Box Revue, but they worked in front of a largely heterosexual audience and would take offense at being called a drag queen. To them, this was a lower classification of the streets and bars and amateur compared to the female impersonation they offered.”

Jeffreys makes a point in classifying the different kinds of drag that occurred at the time. While other female impersonators existed, the drag queens were integral to the new, gay-friendly spaces that began to pop up.

The modern iteration of the drag queen developed in these underground clubs over the next handful of decades. Meanwhile, in the public eye, female impersonation was given a comedic edge; cross-dressing was portrayed in film and TV as a punchline, or an object of strangeness. One classic example is Some Like It Hot (1959), which follows a farcical, almost Shakespearean story of two men posing as women. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Norman Bates is a deranged man who dresses as his mother before killing people. Who could forget the eerie shrieks of the score as the shower curtain pulls back to reveal the poorly styled wig on Norman Bates’s head?

These cinematic forays offered Shakespearean carryovers as well: Twelfth Night and As You Like It, which both carry plotlines involving female impersonation, were adapted into films in the 1930s. There are plenty more examples of this mainstream treatment of drag. But there had to be a point when the LGBTQ+ community’s drag queens strutted back into the spotlight.

Now that we’re venturing into the late 20th century, we can see how drag queens finally began to become a more visible part of arts and culture. Jeffreys told me, “drag was a powerful movement in NYC during the late 1980s and 1990s, due in large part to the explosively experimental East Village performance scene, and its products such as the Pyramid Club and the annual Wigstock drag festival.”

At this point, drag queens were amassing large followings. Some of the first drag icons emerged: Divine was a legend out of Baltimore who frequently worked with the director John Waters. There was something striking about a 300-pound drag queen who gave no f*cks — Divine notoriously consumed dog sh*t on camera at the end of Pink Flamingos. That kind of shock value was intrinsic to the drag persona. Divine’s incredible presence even served as inspiration for Ursula the Sea Witch in The Little Mermaid. According to the story, none of the character designs for Ursula worked, “until an animator named Rob Minkoff drew a vampy overweight matron who everyone agreed looked a lot like Divine.”

And speaking of Wigstock, which Jeffries mentioned in passing above, Lady Bunny is the founder and creator of the event. In Drag Diaries, Lady Bunny tells the story of her first performance in NYC, which speaks to a drag queen’s complete willingness to make a fool of herself. A drag queen challenges you to laugh with her, and laugh at her. That’s what makes her so alluring and captivating. “My first performance in New York was lip-syncing to ‘I Will Survive’ at the Pyramid. I was so inexperienced that the spotlights were blinding me, and I fell off the stage,” she recalled. “I somehow managed to get back up, wig askew and one shoe missing, and finished the number, which was a crowd-pleaser, and I was a fixture at the Pyramid for the next six or seven years.”

Later in that same interview, Lady Bunny talks about how she’d been packaged up as something that was reviled. Again, she captures the fierce, unyielding spirit of someone who is so sure of who they are and what they’re doing that nothing can drag them down.

“I was on 20/20 in a clip that was put out by some religious group trying to show how twisted gays were and how they had to be stopped. They showed footage from Wigstock the year it was in Union Square . . . Then it cut to the women watching the video in some church, shaking their heads and digging in their purses to provide contributions to get rid of me, and people like me. I love that idea. But I’m not going away! They’re going to have to come up with a lot of contributions to get rid of me.”

There are many more historic queens: Australia’s Dame Edna, Pepper LaBeija (often referred to as the Queen of Harlem Drag Balls), and Flawless Sabrina, whose story I heard from the fantastic Zackary Drucker just last year.

As true drag queens came out of the shadows, mainstream media continued to paint more portraits of female interpretation. But there was a notable shift. The drag queen wasn’t quite as much of a punchline, or a garish creature to shine a spotlight on. New films, like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1995), depicted drag queens in more flattering light. There were documentaries in this time, too. LGBTQ+ history was being documented in ways it had never been depicted before.

Paris Is Burning (1990) chronicled the aforementioned Harlem drag balls, where Pepper LeBeija reigned supreme. As we descend into this unfamiliar world, we witness the true artistry of a drag ball, which was like a sporting event for the LGBTQ+ community. These balls marked a safe space for individuals to express themselves and find escape.

But Paris Is Burning offers so much more than that. These subjects, once again, prove what it means to be a drag queen. To be self-assured and to wholeheartedly have an unshakeable faith in oneself. This film offered glimpses into drag culture: we were getting iconic quotes left and right. “Right about now, these next 40 or so years I’m gonna be here,” Pepper LeBeija says. “I’m going to live. And for those children who can’t take the fact that I still look youthful? Ha! Suffer. No bags, no lines. Lovely.”

“Shade comes from reading. Reading came first. Reading is the real art form of insults,” a drag queen named Dorian Corey says in another part of the film. “You get in a smart crack, and everyone laughs and kikis because you found the flaw and exaggerated it, then you’ve got a good read going. I don’t tell you you’re ugly, but I don’t have to tell you, because you know you’re ugly. And that’s shade.” As we’ve moved forward, these aspects of drag culture have only become more prevalent. After all, even RuPaul’s Drag Race has a “reading” challenge every season.

There was also Wigstock: The Movie in 1995, which similarly gave us a look at a safe space for art, love, and self-expression. Here, we could see drag performers truly expressing themselves in a secure and unencumbered way. It marked a new kind of liberation in the drag community, one that drag queens specifically hadn’t experienced before.

Then, of course, there’s RuPaul herself. Perhaps the most well-known drag queen in history, RuPaul has built an incredible empire. RuPaul was hot on the New York scene, but her big break is largely thought to have been the “Love Shack” music video with the B-52s, which was released in 1989. From there, it was a steady climb with 1993’s “Supermodel” video, which positively exploded. But it was also Ru’s ability to stay in the spotlight that ultimately helped her stay relevant. After all, she’s racked up a whopping 65 acting credits over the course of her career.

In 2009, everything changed. With the premiere of RuPaul’s Drag Race, drag queen culture was able to mount a new, more exposed platform. Drag queens were no longer something you had to seek out; no more did fans have to hunt around for local drag shows at gay bars in their cities. RuPaul’s Drag Race gave us a place to see queens in the comfort of our own homes, on a weekly basis. And these weren’t just any queens: they were some of the best America had to offer.

In the near-decade since the series premiere, we’ve seen nine seasons, two all-star seasons, and more than 100 queens. The third season of All Stars is here. Season 10 is right around the corner. If VH1 can keep up the momentum, we may find ourselves in a space where some form of the show is almost always airing. Can you imagine 52 straight weeks of Ru?! We’ll keep our fingers crossed.

It’s not just that RuPaul’s Drag Race gave fans a better opportunity to witness drag. There’s an educational aspect of the show that’s almost impossible to miss. Those who aspire to do drag learn about so many facets of drag culture. Each of these 100 unique queens is helping to establish a broad range of drag styles, aesthetics, and characters.

Source: Read Full Article