Getty Images/E! Illustration

If Meghan Markle wanted to give birth to her first child with Prince Harry at home, she certainly could, with the best doctors and every modern convenience ushered right in with the snap of a royal finger.

It wasn’t too long ago, after all, when that was the norm.

Harry’s father, Prince Charles, was born at Buckingham Palace, as were his brothers Prince Andrew and Prince Edward. His sister, Princess Anne, was born at another royal residence, Clarence House, because Buckingham Palace was mid-renovation to modernize and repair damage sustained during World War II. Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip lived at Clarence House with their two eldest children until 1953.

Hospitals, in one form or another, have existed in England since at least the 11th century, a place for organized healing a logical next step for a civilization perpetually at war. Over the course of the millennium, eventually hospitals also came to be used for pleasant occurrences, such as births, though home deliveries remained the norm into the 20th century. But even though hospitals were vastly improved by the time Queen Victoria birthed nine children in the 1800s, let alone by the time the reigning queen was having babies, Britain’s royal family was content to let the doctors come to them, be they at Buckingham Palace or Balmoral.

Or, in the Queen Mother‘s case… somewhere.

The ninth of 10 children born to Claude Bowes-Lyon and wife Cecilia, Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon—the future Queen Elizabeth and then Elizabeth, Queen Mother—was born on Aug. 4, 1900, but where, exactly, remains a mystery.

Extensive research has been done into where she was most likely born, but since so many siblings had come before her, no one was paying very close attention. Her birth was registered as having occurred in the village of Hertfordshire, at St. Paul’s Walden Bury, one of her childhood homes. But a passport she was issued at the age of 21 cited her birthplace as London and, in 1980, the Queen Mother mentioned having been born in the British capital but christened in Hertfordshire.

Biographer Grania Forbes has suggested the possibility that Elizabeth’s father wrote down the wrong location when registering her birth in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, six weeks after she arrived. Her grandfather noted in his diary that Claude was 10 days late for the start of grouse season at Glamis Castle, the family homestead in Scotland, so it’s at least agreed-upon that she was born in England.

MEGA

It was also surmised that Cecilia went into labor while en route from London, so they pulled over and she gave birth at the home of a doctor in Welwyn, another village in Hertfordshire.

“Conflicting stories—perhaps we shall never know,” said Canon Dendle French, chaplain at Glamis Castle and former vicar of St. Paul’s Walden Bury, who had done his own research on the subject. “But I have to say that London is the least likely place, given the evidence, and I still think it was in, or near, the Bury!”

The really interesting part is that no one thought to ask Elizabeth’s mother to pin those details down for the record—but it just wasn’t a thing one discussed. Though doctors were almost all men, pregnancy and its aftermath were women’s issues. Fathers weren’t even encouraged to be present for the deliveries of their own children—Prince Charles may have been the first male royal in his family to be in the room when his kids were born since Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, watched his wife give birth nine times between 1840 and 1857.

Lisa Sheridan/Studio Lisa/Getty Images

At least tidy records were kept when Elizabeth, at the time the Duchess of York, gave birth. Princess Elizabeth (soon to be the future queen) was born on April 21, 1926, at her maternal grandparents’ house at 17 Bruton Street in Mayfair, London, making her the first monarch to be born in a private home rather than a palace or castle since the Middle Ages. (One-upping her, Prince Philip was reportedly born on a kitchen table at the villa his family was renting in Corfu.) Princess Margaret was born at Glamis Castle on Aug. 21, 1930. Both daughters were delivered via C-section.

The sisters followed the family tradition of home births when they had kids, Margaret having her son, David Armstrong Jones, at Clarence House and her daughter, now Lady Sarah Chatto, at Kensington Palace.

Press Association via AP Images

Princess Elizabeth did do away with a very longstanding tradition, however, when it came to welcoming a direct heir to the throne—the home secretary was not in the room to witness Charles’ birth in 1948, the first time a government minister missed such an occurrence since the 1700s.

To illustrate just how seriously the routine was taken: Margaret was born two weeks late, so then-Home Secretary John Robert Clynes, who arrived in Scotland on time, had to stick around for a fortnight till she arrived. Queen Victoria had at least put an end to a whole coterie of male councilors and aides being in the room, deciding in 1894—when her grandson King George V’s wife Mary was about to give birth to the child who would become King Edward VIII and then abdicate—that the home secretary was enough.

So perhaps the future queen felt that, if protocol dictated that her husband not be there, why should some other fellow get to stay in the room just so he could testify that he was there?

The famously pragmatic Princess Anne was the first to decide that she wanted to give birth in a hospital—and so she did, twice, welcoming son Peter Phillips and daughter Zara Tindall in the Lindo Wing at St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London. When she had Peter, Anne reportedly had a plain private room that cost about $100 a day, or half of what the most expensive hospital room in Britain cost at the time.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

While we could only imagine such excitement today, the queen herself broke the news that she was a first-time grandmother after arriving abnormally late for an investiture at Buckingham Palace.

“I apologize for being late,” she said, per the New York Times, “but I have just had a message from the hospital. My daughter has just given birth to a son.” Then, as per tradition since Buckingham Palace became the British monarch’s official residence in 1837, the birth announcement was posted outside the front gates.

It was in 1977, starting with a smiling Anne, trailed by a pack of nurses and a midwife as she climbed into her waiting car with Peter, that the tradition of delighting the world with its first glimpse of a swaddled royal newborn on the steps of a hospital began. In 1981, Anne carried Zara to the car herself.

But Peter and Zara, though each had a place in line to the throne, were not destined to be monarchs. (They don’t even have royal titles, their mother and first husband Mark Phillips, who was in the delivery room, choosing to give them almost-normal lives instead, without peerages.)

Getty Images

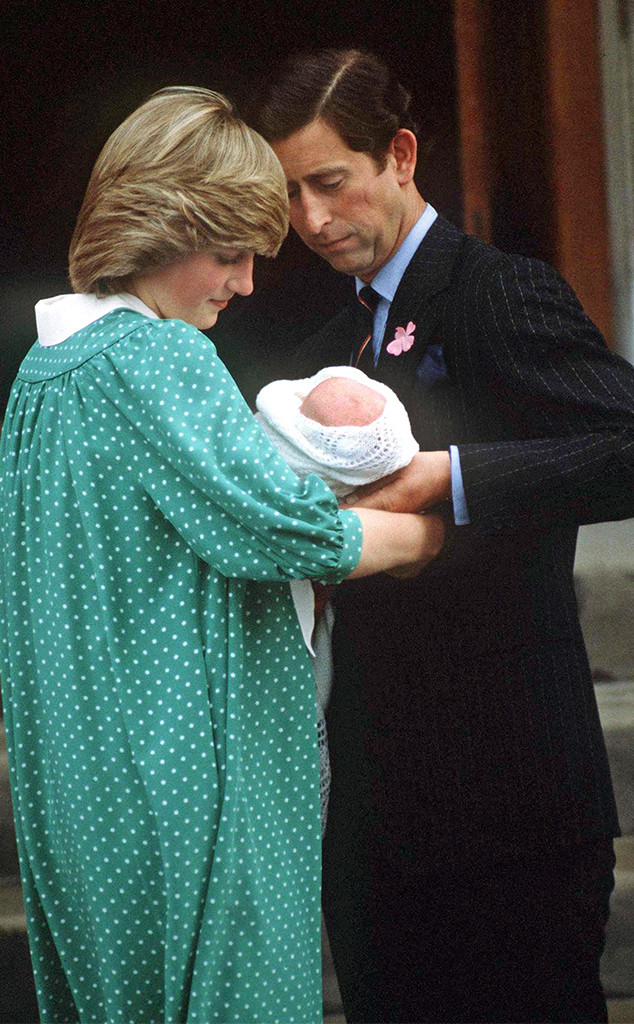

There were no major complications, but Diana (who, like her husband, was born at home, Park House in Norfolk) had suffered through a melancholy pregnancy; she had severe morning sickness and, feeling neglected by Charles, sank into a depression. She later acknowledged throwing herself down the stairs at Sandringham that January; miraculously she wasn’t seriously injured, though she recalled in recordings given to biographer Andrew Morton being “quite bruised around the stomach.”

She was in labor for 16 hours and doctors considered an emergency C-section, but ultimately administered an epidural and she gave birth as she planned. Nurses placed a tiny band around the infant prince’s wrist reading “Baby Wales.”

Unlike his own father, Charles witnessed his son’s birth—”a very adult thing to do,” he described the experience—and a couple of hours later went outside to greet the throng of reporters waiting expectantly for news.

“Is the baby like you, sir?” one asked. “Fortunately no,” the pleased new father said, laughing.

The queen visited, telling the press she was “delighted” (and per biographer Andrew Morton, cracked, “thank goodness he hasn’t got ears like his father”). Then Diana’s mother, Frances Shand-Kydd, and sister Lady Jane Fellowes arrived. Earl Spencer, Diana’s father, said, “He’s the most beautiful baby I’ve ever seen.”

Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

At 6 p.m. on June 22, Diana and Charles introduced William, swaddled in a white lace shawl, to the world. (His name, William Arthur Philip Louis, was actually announced a week later.)

George Pinker, the queen’s surgeon gynecologist who delivered nine royal babies—including Peter, Zara, William and Harry—was among the guests at William’s christening at what then was the spot for royal baby baptisms—the Music Room at Buckingham Palace—as were four nurses who aided the delivery. (Pinker, who died in 2007, became Sir George when he was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1990.) The baptismal water was from the River Jordan, a tradition dating back to the Crusades. The cake served at luncheon afterward was the top tier of Charles and Diana’s wedding cake.

“He certainly has a good pair of lungs,” quipped the Queen Mother when baby William—clad in an heirloom lace christening robe first worn by Queen Victoria’s second child (the future King Edward VII)—gave a piercing wail.

AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth

Some things do not, and have no need to, change, including new-baby humor. Holding his own firstborn son, Prince George, on the steps outside the Lindo Wing in 2013, William noted, “He’s got a good pair of lungs on him, that’s for sure. He’s a big boy, he’s quite heavy. We are still working on a name, so we will have that as soon as we can.”

William had already changed a diaper in those first 24 hours, a far cry from his grandfather Prince Philip, who was working out his nerves with a game of squash and a swim when Charles was being born. He got the happy news that his son had arrived as he was toweling off. The Duke of Edinburgh’s equerry, meanwhile, had procured a bottle of champagne and a bouquet of red roses and carnations to present for the new father to bring to his wife.

Charles, however, was excited to be a hands-on dad, and he changed nappies and gave William baths, throwing the new-baby routine of yesteryear out the window.

Meanwhile, Diana let Charles do the talking when William was born, but 31 years later Kate Middleton chatted with the press a bit outside St. Mary’s. “It’s very emotional, it’s such a special time,” she shared. “I think any parent will know what this feeling feels like.”

The dad humor was on fire, though, with William remarking on George being late, “I’ll remind him of his tardiness when he’s a bit older. I know how long you’ve all been standing here so hopefully the hospital and you guys can all go back to normal now and we can go and look after him.” He said his son had more hair than him, “thank God” and “luckily” looked like Kate, to which his wife added, “No, no, I’m not sure about that.”

Chris Jackson/Getty Images

Also like George, and then Princess Charlotte after him when William took the pair to visit their little brother Prince Louis last year, William gave his first public wave on the steps of the Lindo Wing when his dad took him to visit his new little sibling.

Prince Harry—Henry Charles Albert David—was born at St. Mary’s on Sept. 15, 1984, one week early, and he too was presented to the world the following day before Charles and Diana took him home to Kensington Palace. (Diana’s choices won out with both sons’ first names, while Charles’ preferences, Arthur and Albert, were relegated to middle names.)

Unlike William, however, it’s doubtful that Harry will be returning to the scene of his own birth when his first child is born this spring.

Source: Read Full Article