“You’ll notice we work out next to the bombs,” says Petty Officer Corey Shores, the command fitness leader for the USS North Dakota, nodding at a long metal tube in the submarine’s torpedo room, which doubles as a gym, at least until war breaks out.

This particular MK 48 torpedo is nicknamed Claire, which has been scrawled in marker on the tip by those who may one day stuff it into a launcher and fire it off. Claire carries 1,000 pounds of high-explosive incendiary that is designed to detonate underneath an enemy ship. It’s a powerful reminder of the mission.

“We have four torpedoes on board,” says Shores, a 29-year-old from North Carolina who has a square jaw to match his broad shoulders. He’s primarily a “nuke” who operates the reactor in the North Dakota’s engine room, but Shores also oversees the fitness of the 138-person crew, a “collateral duty” that he takes almost as seriously as his primary mission. He’s a gym rat who volunteered for the job, which required a recommendation from his commanding officer and a five-day training program.

As command fitness leader, Shores is responsible for making sure everyone on the boat passes the semiannual Physical Readiness Test—a sequence of events that measures aerobic capacity, strength, and muscular endurance. He’s also there to ensure that crew members don’t lose their minds, a very real concern when you’re deployed on a pressurized tube of steel that may not surface for three months. And then he’s got to maintain the gym equipment, “which can be a hassle when you’ve got all those guys using one treadmill,” he says.

Thirty people share two showers, two toilets, and two sinks.

Working out is complicated when you’re on deployment. Time is limited, as are facilities. Most Navy ships have large spaces—not to mention open decks—where sailors can break a sweat. Aircraft carriers have gyms, and even basketball hoops that can be rolled out. But the men and women aboard the North Dakota, or any of the other 84 subs in the U. S. Navy’s fleet, lack such luxuries. There is virtually no personal space, and any large space has more than one purpose. It’s not an environment conducive to training.

The sub is 370 feet long, about the length of a football field, and 34 feet across at its widest point. Submariners sleep six to a room no bigger than a walk-in closet; each side has three bunks, and there are just four inches of clearance between your face and the rack above. Sometimes there aren’t enough beds for everyone, so rookies must “hot rack,” or share two beds among three crew members working alternating shifts.

Brian Finke

Thirty people share two showers, two toilets, and two sinks. During the few hours of downtime each day, you can either lie in the environs of your bunk watching movies or playing video games that you loaded onto your phone before deployment, or you can go to one of the larger spaces where people gather: the galley or work zones that double as lounges or gyms.

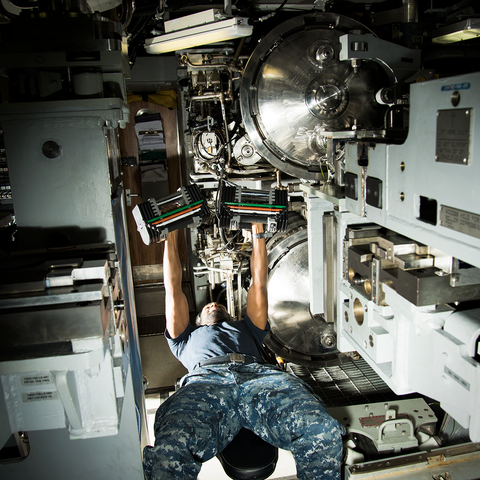

To stay sane and fit, submariners must learn to adapt. Many workouts are conducted in the torpedo room, which isn’t really a room at all. The only places where a six-foot person can stand upright are the passageways. That means most of the activity happens in a space about the size of a utility room under a torpedo rack. The rack can be raised or lowered, but even at its highest point there still isn’t enough room for most people to do a burpee.

The crew keeps its single weight bar under one of the torpedo racks, as well as its two sets of PowerBlocks, an improvement over the old plastic Bowflex weights that cracked too easily and rolled around and got in the way. Even though there’s foot traffic in the room, “you can still do deadlifts and what we call buddy squats,” Shores says. “You put the weight on the bar and two guys hold it—that’s your rack.” Mind you, this is an active work space. Should someone want to do those burpees or some high-knees, they’ll need to step into space that crew members on watch are using to move from one room to another. “They understand,” Shores says, smiling.

The USS North Dakota Workout

Stay in shape with this body-weight workout created by EXOS for the Navy. Do it anywhere — no gear required!

1. Submariners do 5 minutes of dynamic warmup — some mix of jumping jacks, lunges, planks, and high-knees.

PART 1

Descending repetitions ladder

Rest 20 seconds after each exercise. Repeat the entire circuit, laddering down the reps in each movement by 1 in each round. In the final round, you’ll do 5 squats and 5 pushups.

PART 2

Core/triceps circuit

Repeat entire circuit 3 times.

Sailors finish by doing 1 set of body-weight squats to failure, a set of pushups to failure, 60 situps, and about 10 minutes of cardio (typically a mix of jumping jacks, high-knees, quick feet, and jump rope). Once that’s done, they walk for 2 minutes, stretch, and call it a day.

The crew also shares a 35-pound kettlebell, several foam rollers, yoga mats, and TRX straps. There’s a collapsible bench, stored in a cubby, that can be dragged into another narrow space when someone wants to bench-press. There are five cardio machines on board—two spin bikes, a rowing machine, a small elliptical, and a treadmill—and all but one are in the engine room, a top-secret area that is off-limits to visitors.

The most popular, by far, is the treadmill. It’s tucked away in the engine room, under a pipe that’s just out of reach, unless the belt speeds up unexpectedly, causing the runner to jolt forward and smack their head. On other submarines, that pipe is directly above, forcing users to jog with their heads cocked to one side or the other, which submariners jokingly call “combat running.” While the treadmill is in great demand, there are times when it can’t be used.

Fast-attack submarines are multifaceted weapons in the U. S. Navy’s arsenal. They deliver special forces, unmanned aerial and undersea vehicles, and spies around the planet. They’ll also lurk close to foreign ports and intercept communications. All of these missions require stealth, which presents another limitation to fitness. There are periods—during unique missions—when no one is allowed to make any noise. This is called “ultra quiet,” and when the captain announces it, crew members can’t even slam a toilet lid.

“That’s when you would shift to the TRX straps and a lot of body weight,” says Master Chief Kellen Voland, 34, the senior enlisted advisor to the commanding officer of the North Dakota. Voland is a workout fanatic whose enthusiasm, his charges say, is a major reason that no crew member has failed the Physical Readiness Test over the last three six-month cycles.

The Navy Physical Readiness test

With a partner holding your feet, and your knees raised, do as many reps as possible in 2 minutes.

90 great ~ 70 strong ~ 40 average

Rep out for 2 minutes, resting only at the top.

70 great ~ 50 strong ~ 25 average

9:00 great ~ 11:00 strong ~ 14:00 average

· · · Or · · ·

No diving starts allowed.

7:00 great ~ 8:30 strong ~ 13:00 average

These 3 challenges must be completed in the following order, with a break between each sequence lasting at least 2 minutes but no longer than 15. Aim for our metrics.

When Voland visited the torpedo room during the last deployment, it was consistently crammed at certain times. “There would be a guy on the bike, a guy waiting for the bike, a guy doing pushups, and a guy doing TRX,” he says. “There’d be guys doing bench press, and the torpedo man on the watch would have to step over them to do his job.”

Submarine interiors aren’t designed with fit and finish in mind. The metallic guts of the rooms are exposed, and the myriad pipes and rails are perfect makeshift gym bars or latch points for TRX straps. “As long as they’re nice and sturdy,” Voland says, reaching up and grabbing a hatch handle to do a pullup. “You have to use the space and the tools that are available. I adapt and overcome and work out a lot of stress and anger down here.”

He laughs as a memory pops into his head. “I’ve had them run fire drills down here while I’m in the middle of a workout, and I’ve had to move out of the way to let guys run through to fight the fire—and then you just move back and keep doing your thing.” Working out helps the crew forge physical fitness and soothes stress, but sometimes all that training is not enough.

All submarine movements are classified. The Navy doesn’t even release precisely when a sub will leave or arrive in port. In late 2017, when Men’s Health visited the North Dakota at its base in Groton, Connecticut, we were told only that the sub would be deploying soon. It left port shortly after our visit and was only a few days into that tour when something terrible happened less than 200 nautical miles out in the Atlantic Ocean. On January 12, a young petty officer attempted suicide. The man shot himself with a rifle (not fatally), but neither his name nor many details of the events that followed have been released.

A lot of what we know about the incident was revealed in a Facebook post written by the North Dakota’s commanding officer, Mark Robinson. An evacuation plan was set in motion, and turbulent conditions in the Atlantic required the sub to head full bore toward the Connecticut coast, where around midnight it rendezvoused with a tugboat at the mouth of the Thames River in thick fog.

“It was the worst weather I’ve ever seen for something like this,” Robinson reported. Once the injured sailor was alert, some of his crewmates sat at his side, holding a phone so he could watch music videos during the painful seven-hour trip to safety. Areas inside the sub were disassembled so a stretcher could pass through more easily, and crew members assisted Navy firefighters in getting the stretcher out through the sub’s weapons hatch. Some of the submariners secured themselves to the deck outside, forming a “human safety net” to protect paramedics helping to transfer the man to a tugboat and finally to an ambulance on shore. “I can’t truly express the amount of heroism I saw in the last 48 hours,” Robinson wrote. “As a result, the Sailor is recovering from surgery in a hospital in New Haven with his parents by his side.”

The Navy didn’t speak further — not surprising, considering that submariners dedicate themselves to the so-called Silent Service — but it was a jarring, very real example of a subject that was talked about when Men’s Health toured the North Dakota and the U. S. Navy Submarine School. Just as the crew members train their muscles, they also train their minds and build resilience.

You have to look at people holistically and understand that having a bad day is normal.

Commander James Rapley, M.D., the force psychiatrist for Submarine Forces Atlantic, is the man charged with managing mental health for crews on the 35 East Coast–based subs. He likens the mission of diving deep to getting on a spaceship. It’s an utterly alien lifestyle, unlike anything else in the military or on earth. There’s no sunlight, and water and air are produced on board. The sub’s complex systems provide breathable air and drinkable water, but the former smells “unique,” Dr. Rapley says, and the latter tastes crisp but is low in minerals.

There’s limited email and no Internet or phone contact for the crew underwater. When crew members kiss their family and temporal reality goodbye at the docks, they cross over into a bizarro world where days are just semantic; the only thing that distinguishes “Sunday” from “Monday” is the menu in the kitchen. “I could really screw with people by changing that,” says Lance Cross, chief culinary specialist on the North Dakota.

Just keeping the sub from sinking requires the focused work of everyone on board. Strangers are forced to become intimately close, because there are no secrets. “You know everything about everyone,” says Dominic Sisto, 26, a navigation electronics technician who served aboard the USS Columbia and is now assistant command fitness leader at the U. S. Navy Submarine School. “You might not like a person, but you have to trust what he or she is doing on watch. You have to trust everyone. You rely so much on people, you have to open yourself up almost like a marriage.”

But that trust only goes so far. Chatting about vulnerabilities is not something sailors are accustomed to. Some view psychological struggles as a weakness, which dissuades sailors from seeking help, Dr. Rapley says. The Navy is trying to reverse that old-school thinking. “You have to look at people holistically and understand that having a bad day is normal,” he says. “Having issues that you need to correct is normal.”

Dr. Rapley has helped roll out an “embedded mental-health” program to improve personnel’s “psychological fitness” and slash the stigma of psychological struggles. “A big part of ensuring mental and spiritual health is creating a community,” he says. There are mental-health professionals purposely placed on the waterfront, where the boats dock, who are in regular contact with each sub’s command staff. Submariners are encouraged to visit those therapists and are treated, Dr. Rapley says, with “a holistic approach to mental health and performance enhancement” that involves focusing on mind-set and assessing diet, exercise, physiology, hormonal and neurotransmitter balance, and metabolism. Treatment sometimes goes beyond talk therapy to include nutritional changes, exercise, and, if nothing else works, medication.

At sea, there are no dedicated mental- health pros, so the sub force’s psychiatrists now run an executive coaching program for key leaders, including the captain, executive officer, independent duty corpsman, and chief of the boat — the senior-most enlisted person on a crew, such as the North Dakota’s Kellen Voland. COBs are critical because they have the most day-to-day interaction with junior members of the crew.

A primary focus of the coaching, Dr. Rapley says, is teaching command leaders like COBs how to look out for stress in that population. The most common signs, he says, are irritability, anger, sadness, excessive worry, decreased motivation and work ethic, poor attentiveness, insomnia, and poor time management. The Navy wants sub leaders to recognize these signs before they’re a problem and, Dr. Rapley says, try to “reframe the demands of military life to focus on success/winning as opposed to the potential for failure.” The result, he hopes, will make crew members more “resilient and tough,” Dr. Rapley says.

Before embedded mental health was introduced, the sub force lost the equivalent of two full crews a year because of psychological issues—either to medical discharge or to other jobs in the surface fleet. Now, by letting submariners know they can get better and return to work, there’s been a 50 percent decrease in “unplanned losses” across the force, Dr. Rapley says.

Motivational techniques and performance psychology have been big parts of this improvement, and so has creating an “extended support network,” from the therapists in port to the command leaders. Dr. Rapley says that every crew experiences a few days where things are intense and emotions are running high, but that quickly settles by necessity. “The spectrum of emotion becomes much tighter,” Dr. Rapley says. “You rarely have people losing their cool or yelling, which is very different from surface ships where you’ve got the room to act out and yell and then go and get space to calm down.”

Prior to 2014, submariners operated on an 18-hour workday while underway. Everyone worked a six-hour watch shift, followed by a 12-hour break, the theory being that submarine duties required such intense concentration, and allowed so little margin of error, that a six-hour shift seemed the most sensible.

But the regimen changed after crews heeded the advice of scientists who had been studying the watch schedule at the Naval Undersea Medical Institute in Groton. “We went to eights for circadian-rhythm sleep cycles,” says Voland. “I thought the eights were going to be too much, but if you ask the new kids coming on, they love ’em.” As a former sonar tech responsible for staring at a monitor, Voland was concerned about screen burnout. But today’s teenagers, reared on digital devices, aren’t bothered in the slightest. “From a stress-management perspective, from a fatigue perspective, the eights have made a difference,” he says. And it’s created more time for working out.

It’s not just about you being healthy; you can’t be a danger on the boat.

A person finishing an eight-hour shift has 16 hours of free time instead of 12, which is important because boat responsibilities don’t end after a watch. Most crew members have collateral duty of some kind, and if not, they’re cleaning. Submariners must qualify for their “dolphins,” which are given to those who have demonstrated proficiency in all of the sub’s major systems—including the ability to respond to emergencies, such as flood, fire, and toxic air. You don’t have to become an electrician, but you need to know enough about electricity to fill in. For the first year a new sailor is on a sub, they’re studying for this test, on their own time. “A guy gets off a watch, does an hour of cleanup, an hour of training, does some maintenance; that’s probably four hours. He still has 14 hours to sleep, work out, train, study, qualify,” says Voland.

As the man responsible for submarine force health, Commander Thomas Baldwin, force medical officer for Command Submarine Forces Atlantic, has to worry about many facets of submariners’ well-being. (In his personal life, he and his wife won the 2017 SuperFit Games male/female team title in the 50+ age group in the Masters category.) Unlike in his previous job, which included working with SEAL teams, he’s now dealing with a different group of sailors, who operate in dark, confined spaces. Muscle atrophy can set in as soon as three weeks into a deployment, he says, and a loss of aerobic capacity is almost inevitable because there are such limited workout options due to space.

Submarine culture is blunt about its fitness requirements. “It’s not just about you being healthy; you can’t be a danger on the boat,” says Sisto, who harps on fitness to new recruits. “I tell them that if you can’t do 45 pushups or if you weigh too much, I might not be able to carry you to safety in a casualty event. That’s what’s scary. It’s like, ‘Dude, if something happens, I literally can’t save you.’ ”

Crew members are trained to save a disabled mate by using the fireman’s carry. “If a submarine goes down, God forbid, I want to be able to swim to shore,” says Petty Officer First Class Eric Chapman, a 26-year-old sonar tech from Mississippi. “What if you have to save someone else and you aren’t strong enough? Are you going to let him die? You have to make them look at it that way or they don’t understand.”

One of the most intense evolutions in Groton is the Pressurized Submarine Escape Trainer, which prepares students for the worst-case scenario: bailing out of a disabled submarine and reaching the surface. This training comes very early, within a few days of arriving from boot camp. A seal on the wall above the 37-foot-high, 84,000-gallon tanks bears these words: “When all else fails, you won’t.”

“It puts them in a stressful situation right away,” says Lieutenant Commander Warren Ross, one of the two undersea medical officers who oversee safety at the facility. Escape from depth is the last resort that no one wants to attempt, but it is possible from as far down as 600 feet because of the orange survival suits that shield a submariner from the cold while providing enough air to reach the surface. The suits have never been used in a real-world event, but the point of the training is to build confidence and show recruits that they work. “That’s what we reinforce here,” Ross says. “Trust your training, trust your equipment.”

The end result is that a recruit masters every system on the boat. The job comes with tremendous responsibility. “We take 7,800 tons of equipment out to sea,” says Kyle Calton, the bespectacled executive officer of the North Dakota.

“We have 19-year-olds responsible for torpedoes with a thousand pounds of high explosive in them, guarding, maintaining, and being able to shoot the weapons at a moment’s notice” — something they should be able to do in two minutes or less when ordered to fire. “Physical fitness is a big part of that.”

Source: Read Full Article